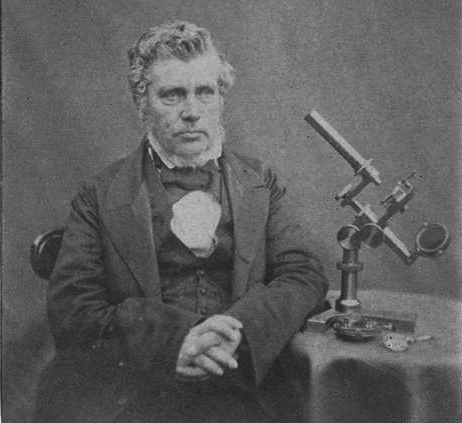

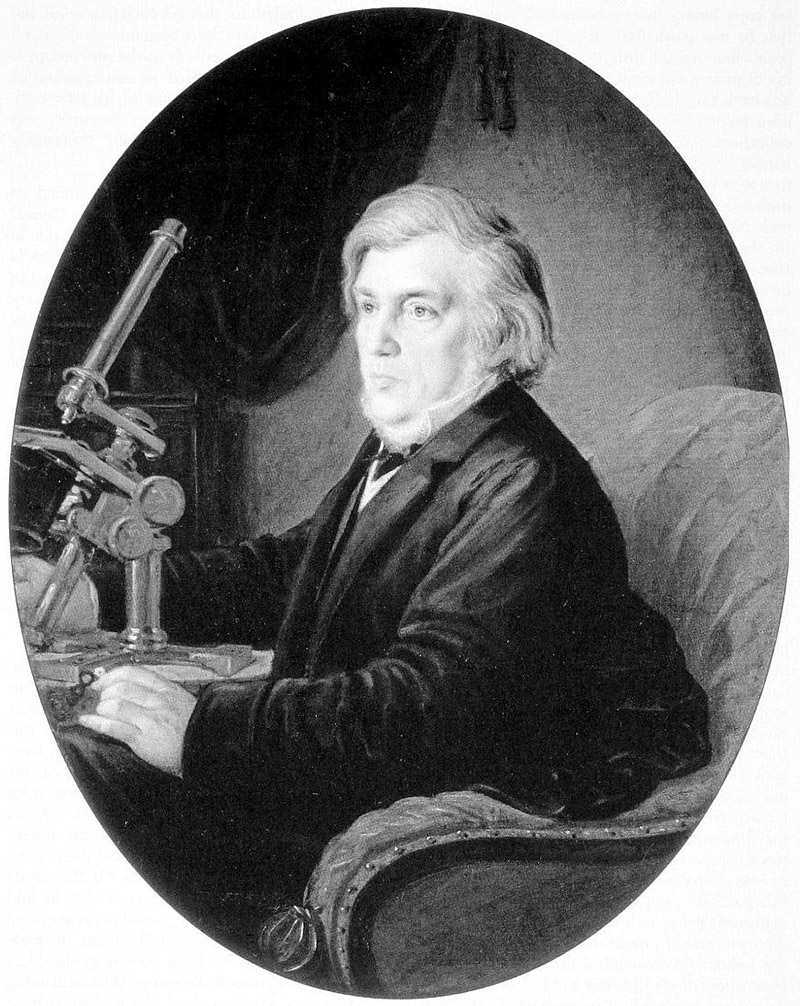

Figure 1. Andrew Prichard, 1843. Daguerreotype by A.F.J. Claudet. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an image in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Andrew Pritchard, 1804 - 1882

by Brian Stevenson

last updated January, 2023

Andrew Pritchard made numerous, substantial impacts on microscopy during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Soon after completing his apprenticeship, Pritchard received acclaim for his production of microscope lenses that were made of diamond, sapphire, and other jewels. The best of these jewel lenses produce little-to-no chromatic aberration. Catapulted by that success, Pritchard built a broad retail and publishing business.

Pritchard’s various products are described below in 5 sections: (A) microscopes, (B) microscope slides, (C) microscope accessories, (D) books, and (E) catalogues, price lists, and advertisements. Two contemporary summaries of Andrew Pritchard’s life follow those sections.

Important dates and locations:

1825: Pritchard was described as an “assistant” to Cornelius Varley. He was then 21 years old, and would have recently completed his apprenticeship with Varley.

1827: Pritchard was described as working for himself, from 18 Picket Street, Strand.

1829: Between February and May, 1829, Pritchard changed his business address to 312 Strand. By 1832, his business address had reverted to 18 Picket Street, Strand

1834: Last known record of Pritchard at 18 Picket Street.

1836: First known record of Pritchard at 263 Strand.

1838: Pritchard relocated to 162 Fleet Street

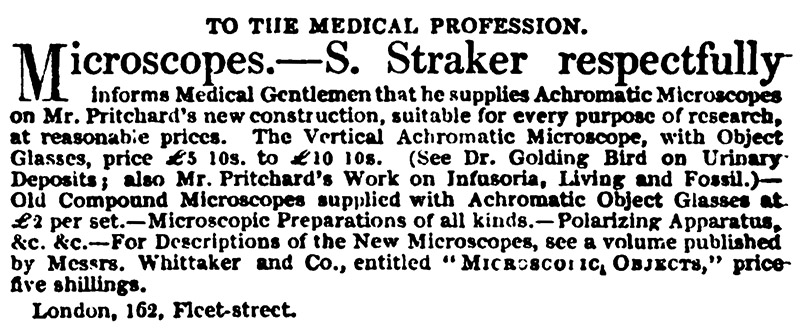

1849: Samuel Straker (ca. 1813 - 1889), Andrew Pritchard’s brother-in-law, took over management of the optical business.

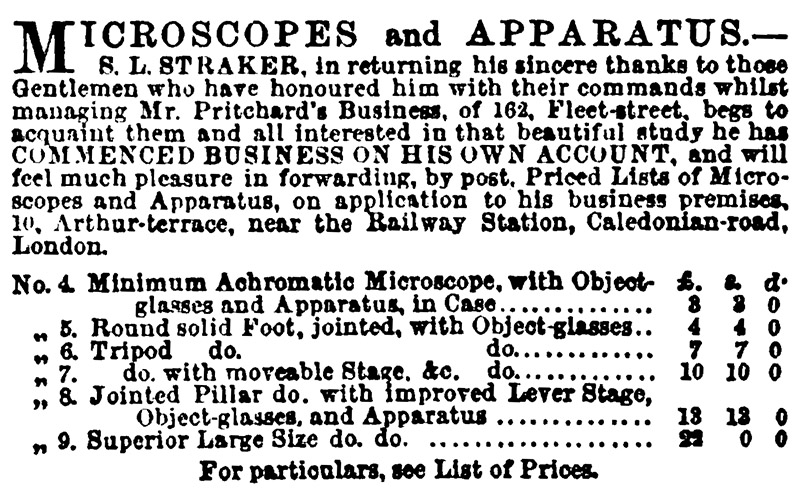

1855/6: Straker left to open his own shop elsewhere. Pritchard appears to have kept his shop open until 1858, on a part-time basis.

Figure 1.

Andrew Prichard, 1843. Daguerreotype by A.F.J. Claudet. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an image in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

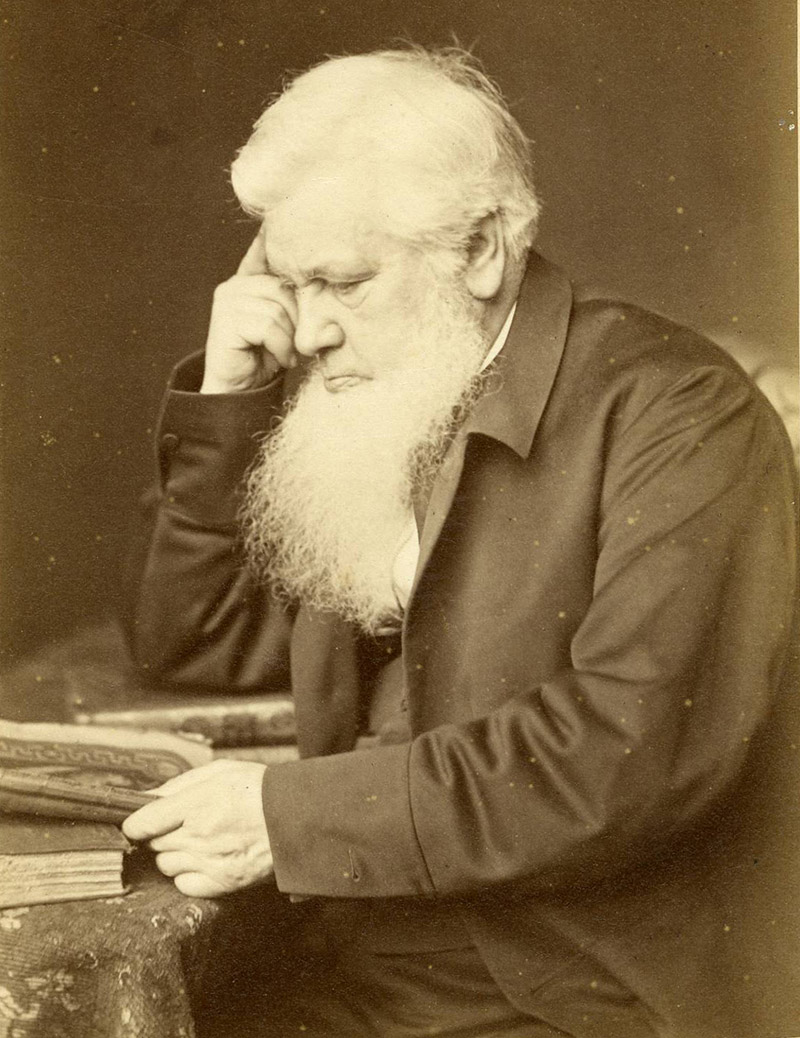

Figure 2.

Undated photograph of Andrew Pritchard with one of his microscopes. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an image in the National Museum of Science and Industry (U.K.).

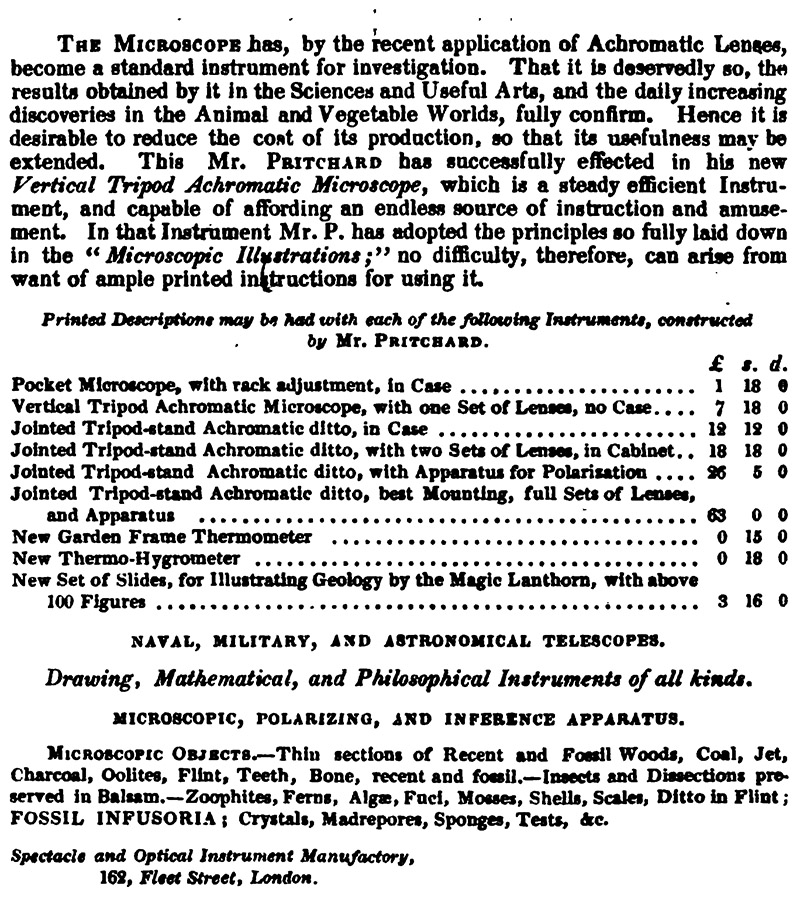

A. Microscopes

As with other microscope manufacturers/retailers, Andrew Pritchard's earliest instruments were probably produced by his own hand. As the business increased, brasswork and optics would have been assigned to in-house craftsmen or outsourced to subcontractors. For example, Pritchard is known to have contracted lens production to Hugh Powell and Camille Nachet (Nuttall, 2006).

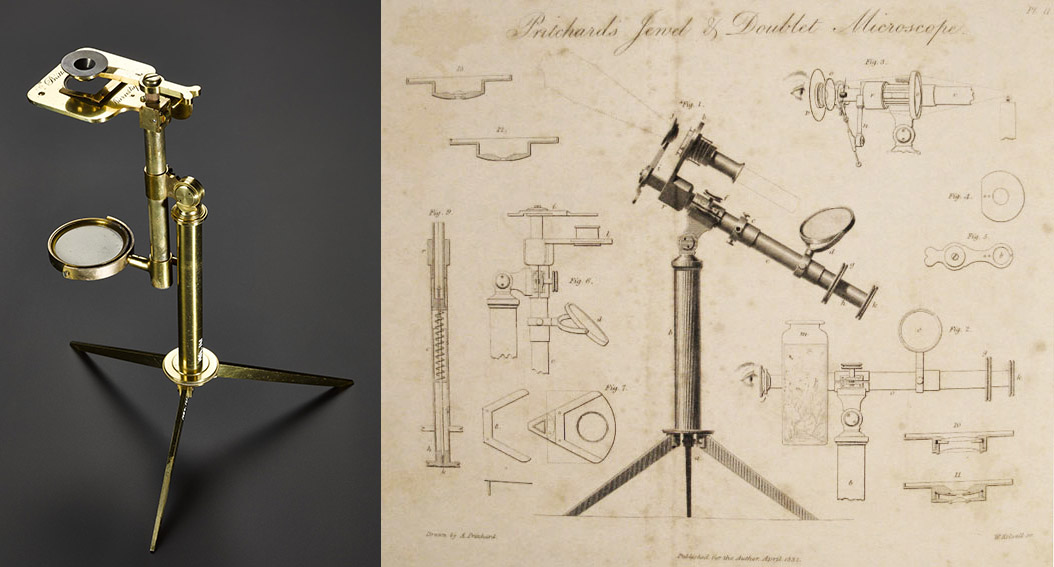

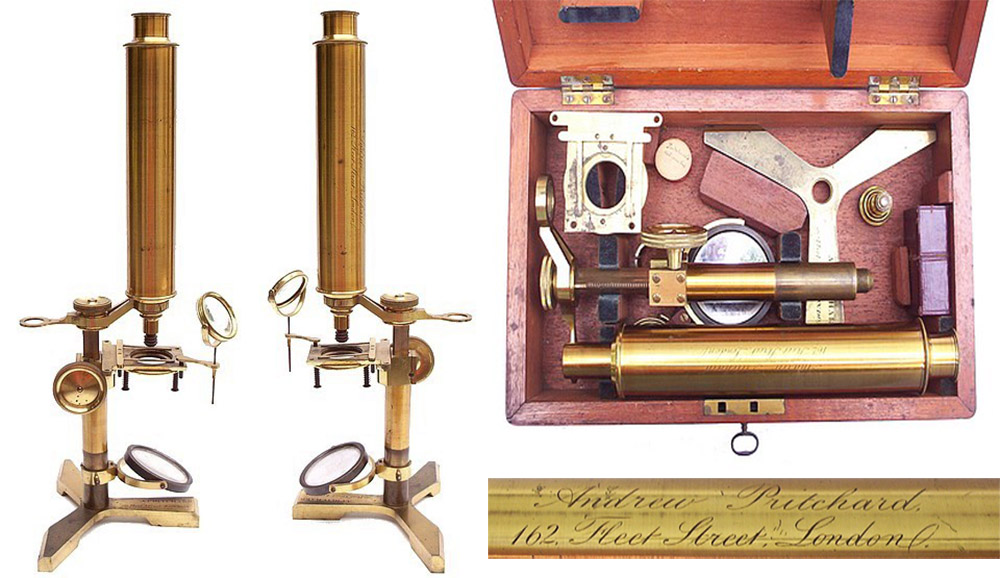

Figure A1.

Circa 1830 simple microscope, as described in Pritchard and Goring's 1832 "The Microscopic Cabinet of Selected Animated Objects: With a Description of the Jewel and Doublet Microscope, Test Objects, &c". This example is signed by William Britton of Barnstaple, Devon, who was certainly a retailer, not a manufacturer. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/collection-search-results/microscope-simple/222058.

Figure A2.

Circa 1830 simple microscope, signed, "Pritchard, 312 Strand". Pritchard began using that address in 1829, then changed it back to 18 Pickett Street in 1832. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

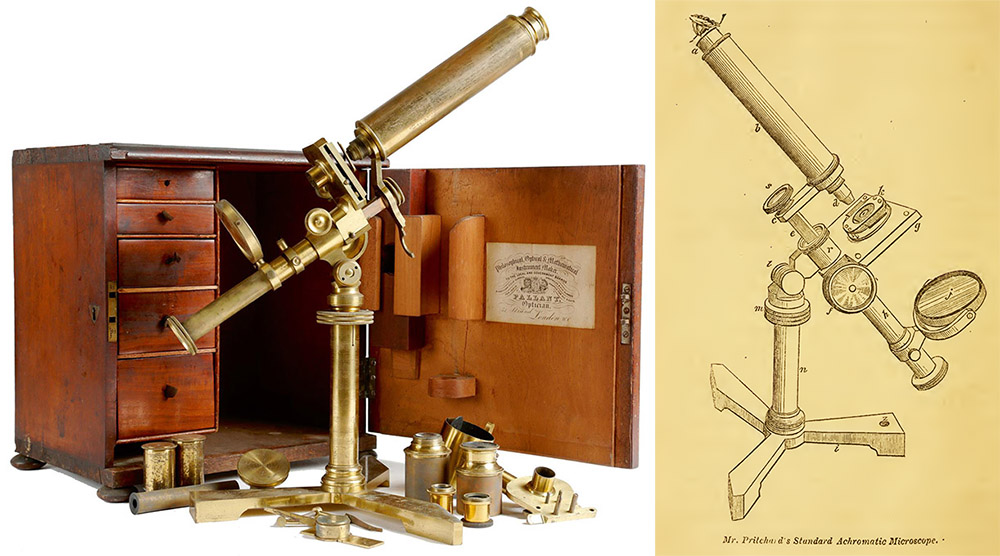

Figure A3.

Circa 1833 "Standard Achromatic Microscope" (also known as the "Achromatic Engiscope"), signed on the foot, "Pritchard, Picket St., London". He traded from 18 Pickett Street between 1827 and 1834/6. The cabinet has a label indicating that it was re-sold by one John Pallant. The image on the right is from Pritchard's 1847 "Microscopic Objects". This model was also described in his 1834 edition of "The Natural History of Animalcules", but not in his 1830, first edition of "Microscopic Objects", implying that production of this popular model started between 1830 and 1834. Microscope photograph adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

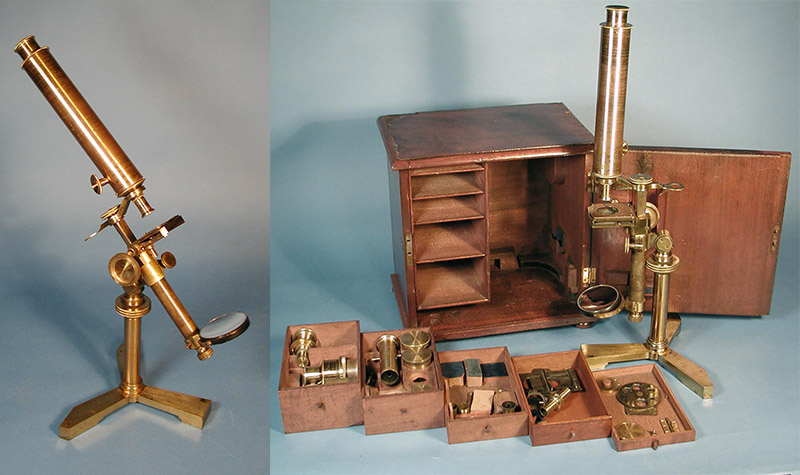

Figure A4.

Circa 1835 "Standard Achromatic Microscope". It is signed on the foot, "Pritchard, Picket St., London", and on the tube "Andrew Pritchard, 263 Strand, London". He traded from 18 Pickett St. between 1827 and 1834/6, and 263 Strand between 1834/6 and 1838. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure A5.

A variation on the "Standard Achromatic Microscope", signed on the foot and the tube "Andrew Pritchard, 263 Strand, London", dating it between 1834/6 and 1838. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=5956&TitInventoryNo=42721.

Figure A6.

Pritchard's "Traveller's Pocket Microscope". It was described in 1831 as "an exceedingly convenient little instrument, furnished with all the requisite magnifiers, mirror, forceps, and rack and pinion adjustments, packs into a case only 2 1/2 inches long by 2 inches wide, without being taken to pieces, whereby much trouble is saved; and the risk of injury by misadaptation of parts, whence damage frequently occurs to optical instruments, is avoided." The illustrated example is engraved with the address of 263 Strand, dating it to between 1834/6 and 1838. The image on the right is from Pritchard and Goring's 1832 "The Microscopic Cabinet of Selected Animated Objects: With a Description of the Jewel and Doublet Microscope, Test Objects, &c". Microscope images adapted by permission from http://www.microscope-antiques.com/pritchard.html.

Figure A7.

Circa 1838 "Standard Achromatic Microscope". The foot is engraved with Pritchard's name and the address 263 Strand, London, where Pritchard worked between 1834/6 and 1838. The body of the microscope is engraved with Pritchard's 1838-1856 address, 162 Fleet Street. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure A8.

Circa 1845 "Standard Achromatic Microscope", illustrating its use as either a compound or simple microscope. The accessory drawer holds four each simple and compound objective lenses. The body is engraved with Pritchard's 1838-1856 address, 162 Fleet Street. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure A9.

Circa 1840 "Simple Achromatic Microscope", which was described in both the 1838 and 1845 editions of "Microscopic Illustrations" (see Figure D3, below). The cabinet contains both simple and compound objective lenses. The body tube is engraved with the name of a retailer, "A. Dodd, 36 Glassford St, Glasgow". Adapted by permission from https://microscope-antiques.com/pritchardport.html.

Figure A10.

Circa 1840 "Simple Achromatic Microscope", without the tilting option seen in Figure A9. The cabinet contains both simple and compound objective lenses. The round foot is engraved with Pritchard's name and his 162 Fleet Street address. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet sale site.

Figure A11.

Another circa 1840 "Simple Achromatic Microscope", with a tripod foot. The body tube is engraved with Pritchard's name and the address 162 Fleet Street. Adapted by permission from http://www.antique-microscopes.com/mics/pritchard.html.

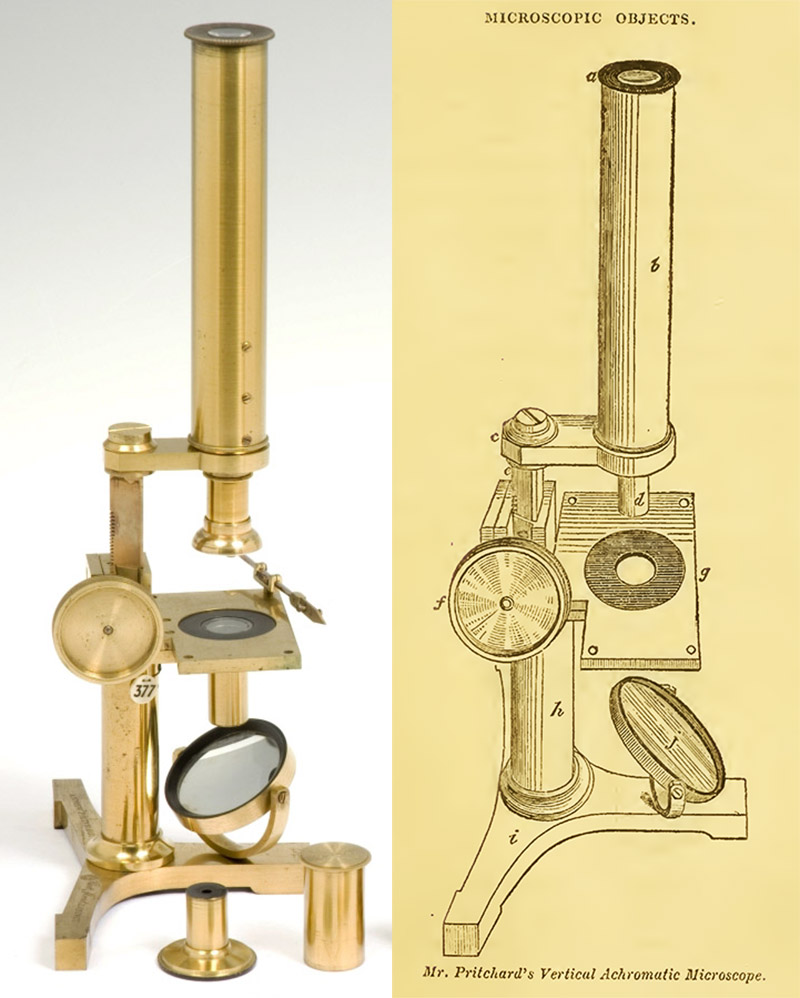

Figure A12.

Another style by Pritchard, the "Vertical Achromatic Microscope", so-named because it does not recline. The surviving microscope bears his 162 Fleet Street address (after 1838). The engraving on the right is from Pritchard's 1847 book, "Microscopic Objects". Microscope image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=6999&TitInventoryNo=42376.

Figure A13.

Also engraved with the Fleet Street. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?thumbnails=on&irn=5915&TitInventoryNo=53541.

Figure A14.

Another microscope of the model shown above, which includes an accessory arm for holding a light source. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8626781/compound-achromatic-microscope-compound-microscope.

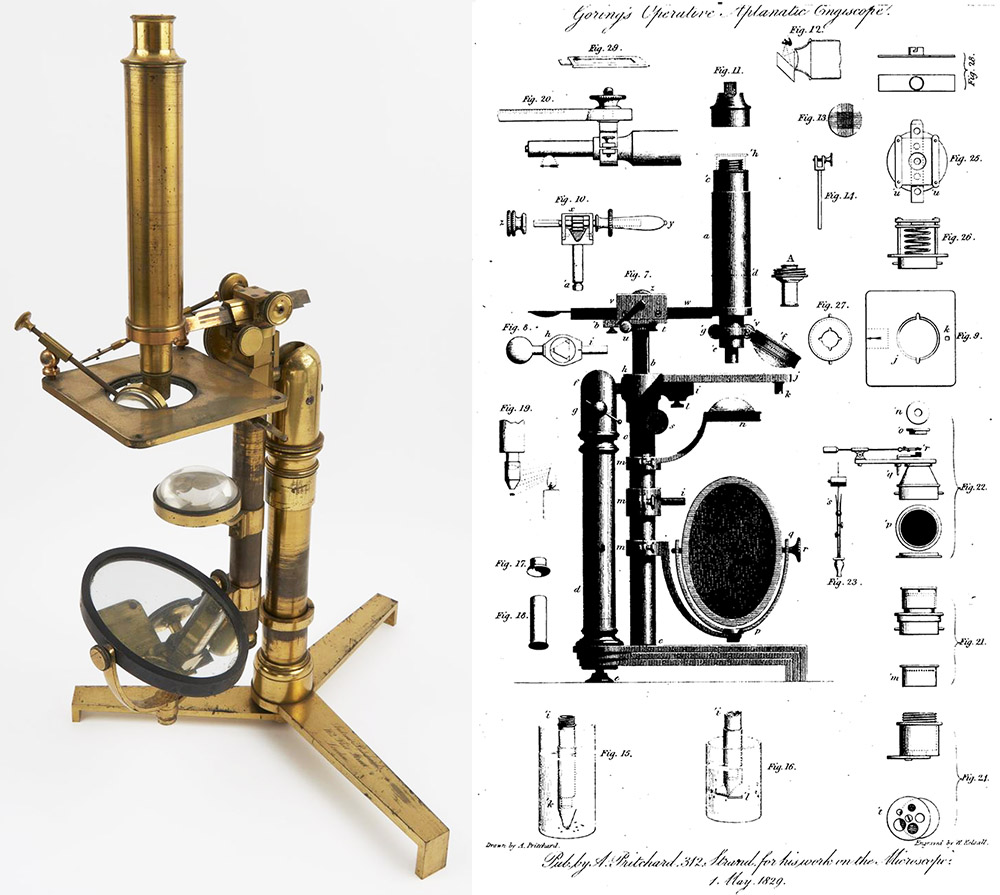

Figure A15.

A Goring-designed "Operative Aplanic Engiscope", signed on the foot by Andrew Pritchard and "162 Fleet Street", dating it to after 1838. The engraving on the right is dated 1829, and was printed in Pritchard and Goring's 1830 "Microscopic Illustrations". The same illustration was included in their 1845 edition of that book, indicating that Pritchard manufactured this model from at least 1829 until well into the 1840s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from https://collection.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects/co8038/gorings-operative-aplanic-engiscope.

Figure A16.

A very large "Achromatic Microscope / Engiscope", signed on body tube with Andrew Pritchard's name and "162 Fleet Street". Unlike the vast majority of Pritchard's instruments, this one bears a serial number, 560. It probably dates from toward the end of Pritchard's microscope-making career, likely after 1850. Adapted with permission from http://www.microscope-antiques.com/bigpritchard.html.

Figure A17.

Two achromatic objective lenses, manufactured by Camille Sébastien Nachet (1799-1881) for Andrew Pritchard. Nachet began his business in 1839, initially as a producer of achromatic objectives, so these lenses probably date from ca. 1840s. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposs from an internet auction site.

B. Microscope slides

Andrew Pritchard also sold microscope slides, many of which bear his name. These are occasionally seen at auction, and often command high prices. However, Pritchard probably did not personally make these slides, but instead had them custom-made for his retail shop. Indeed, most microscope manufacturers did not make the slides that they sold. For example, Pritchard brought in slides that were manufactured by Joseph Bourgogne, with whom he was friends (Figure B3).

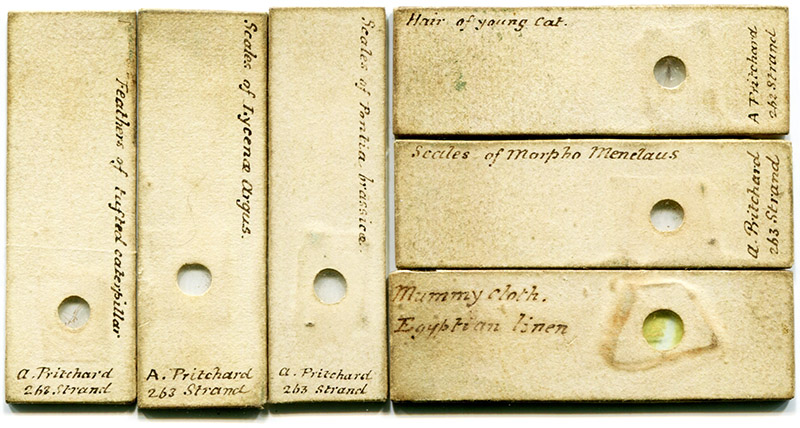

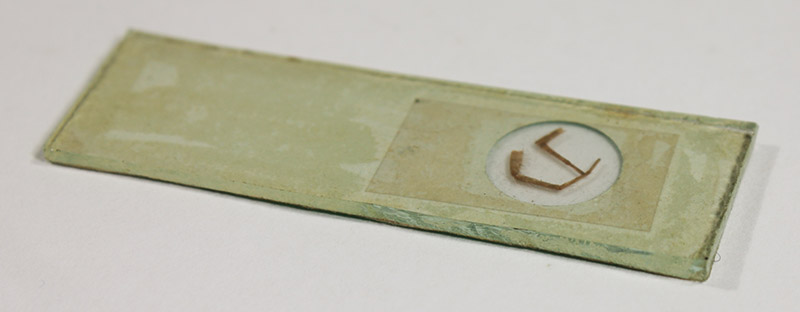

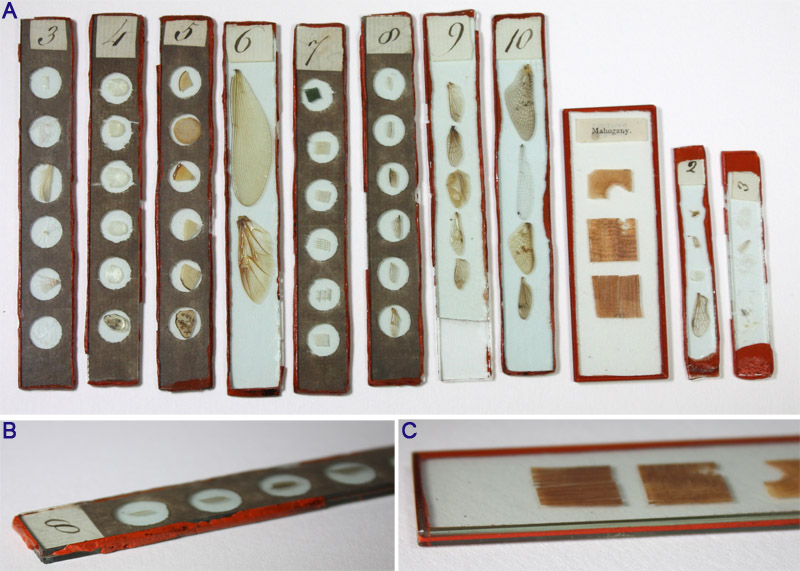

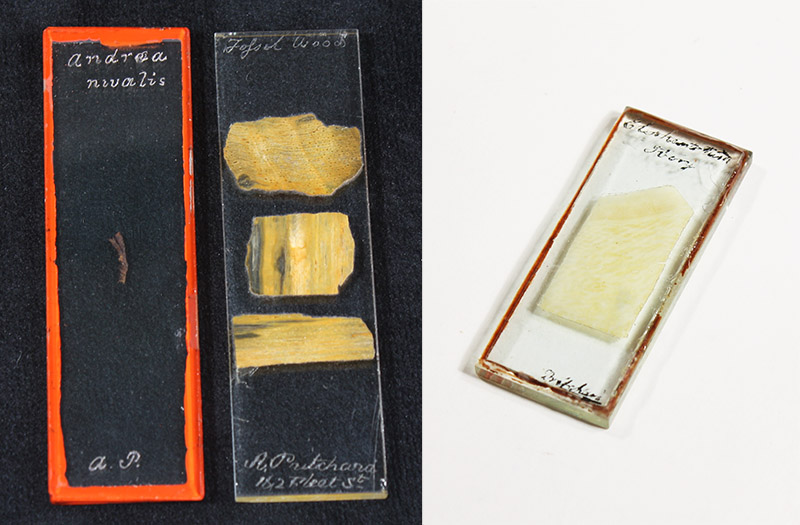

Figure B1.

Ivory sliders that are printed with Pritchard’s name and specimen descriptions. The slider on the left also bears the address of 263 Strand, dating its production to between 1834/6 and 1838. Sliders with a maker’s or seller’s name are exceedingly rare, so these were likely produced for very special purposes. Images adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from internet auction sites.

Figure B2.

Microscope slides with Pritchard’s 1834/6 - 1838 address of 263 Strand. They are approximately 2 x 1/2 inches in size, with cream-colored paper glued on the front and sides. Most are dry-mounts with mica cover slips. The exception is the lower right slide of "Mummy cloth, Egyptian linen", which is mounted in balsam under a glass cover slip. Professional slide-makers John New and James W. Bond began mounting specimens in Canada balsam circa 1832.

Figure B3.

Microscope slides labeled with Pritchard’s 1838-1856 address of 162 Fleet Street. Left, a circa 1840s dry-mount of Norfolk Island pine wood sections, comprised of two glass slips of the same thickness, sealed with yellow paper covering. Center, two circa 1850 slides by Joseph Bourgogne, the specimens mounted in balsam. Right, a standard-size (1x3 inch) balsam mount of guano diatoms, circa 1850s.

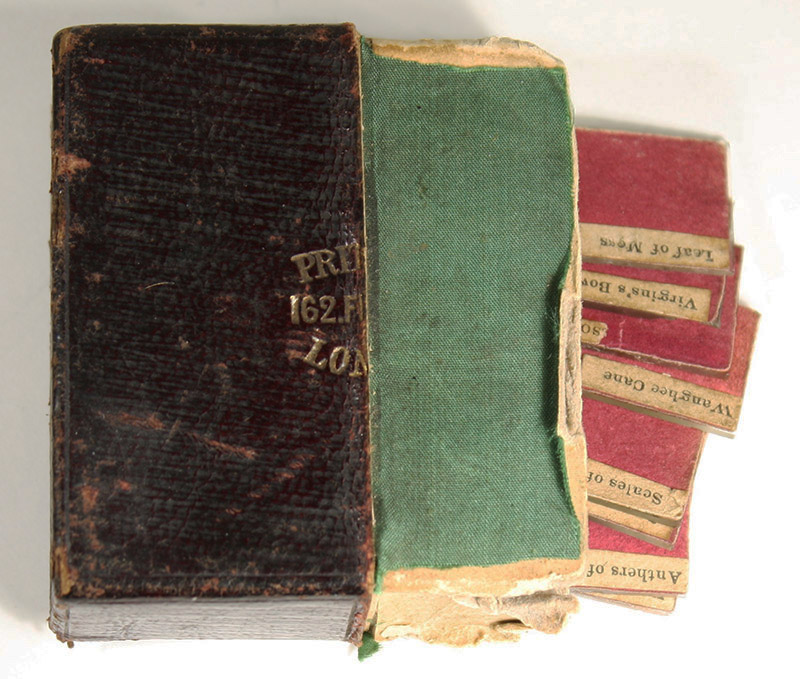

Figure B4.

A boxed set of 16 microscope slides, sold by Andrew Pritchard, ca. 1835. The small slides are approximately 2 x 5/8 inches (5 x 1.6 cm). The case measures 2 1/4 x 1 1/4 x 7/8 inches (5.7 x 3.4 x 2.4 cm). Although it has been noted that some of Pritchard’s microscope books included lists of objects that could be cut out and used as slide labels, the printing on these slide’s labels does not match that in his books. The labels were most likely provided to the slide maker as printed sheets. All of the slides are dry-mounts, the coverslips are sheets of mica, and the glass is rough-cut.

Figure B4-B.

A boxed set of 2 dozen microscope slides, sold by Andrew Pritchard, ca. 1835.

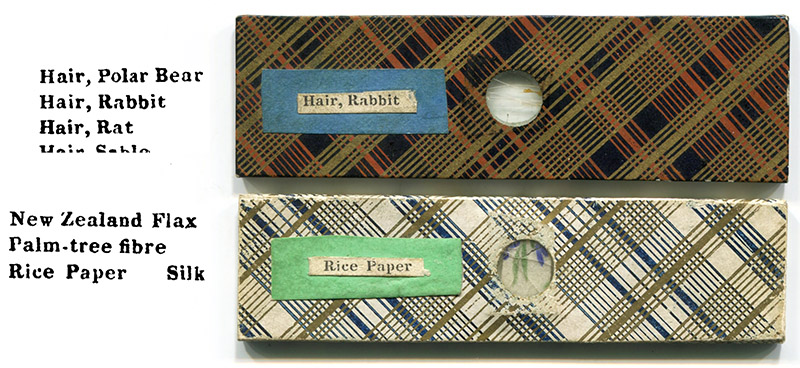

Figure B5.

A partial boxed set of microscope slides, sold by Andrew Pritchard, ca. 1840. The case is stamped with his name and address of 162 Fleet Street (lid is missing). The small slides are approximately 2 x 5/8 inches (5 x 1.6 cm). The case measures 2 1/4 x 1 1/4 x 7/8 inches (5.7 x 3.4 x 2.4 cm). All of the slides are dry-mounts, the coverslips are circles of mica, and the glass is rough-cut. The printing on the labels does not match the font or layout used in any of Pritchard’s books of microscopy.

Figure B6.

A two-shelf wooden cabinet of microscope slides, sold by Andrew Pritchard, ca. 1840. The lid bears an ivory label printed "Microscopic Cabinet", harkening to Pritchard’s 1832 book with that title. The small slides are approximately 2 x 5/8 inches (5 x 1.6 cm). The specimen labels are identical to those printed in the 1835 and 1842 editions of Pritchard’s book, "Two Thousand Microscopic Objects". That helps date this cabinet and slides to the 1830s or early 1840s. The coverslips are rectangles of mica, and the slides have papers covering the edges, a much finer finish than the slides in Figures B4 and B5.

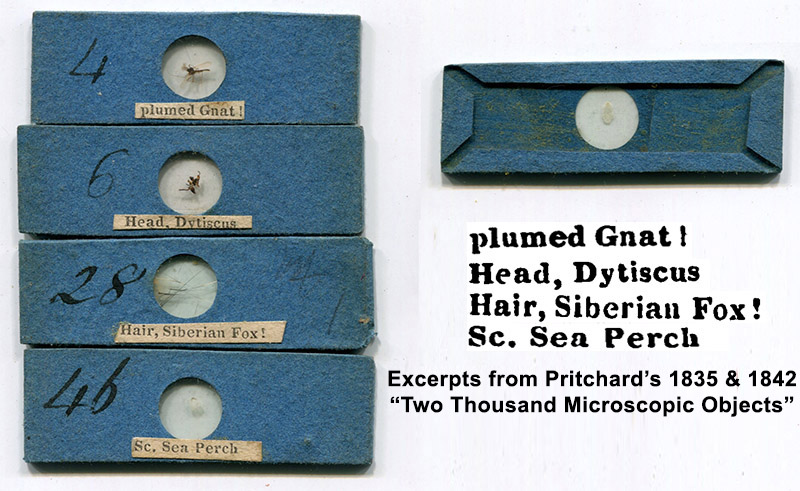

Figure B7.

A pair of home-made microscope slides that used specimen labels from Pritchard’s 1835 / 1842 "Two Thousand Microscopic Objects". Both slides are roughly 1 x 3 inches.

On the use of sealing wax and "Pritchard slides"

A type of microscope slide to which Pritchard’s name has become attached consist of two glass slides of the same size, the specimen(s) dry-mounted between, and the edges sealed with red wax (Figures B8, B9, and B11). Such slides are occasionally found with Pritchard’s name printed on a slip of paper that is fixed between the glass slides. Pritchard also described production of such slides in his 1842 Microscopic Objects. These associations have led to a common perception that Pritchard actually made those slides. While Pritchard retailed the slides that have his name attached, there are significant reasons to doubt that he made those or any of the other slides sealed with red wax, or that he was the only source of such slides.

The first known method in which wax is used to seal the edges of two glass slips was published by Charles Gould in 1829: "to preserve curious objects, they may be fixed on some slips of glass with gum-water, and another glass placed over them, cemented together with sealing-wax" (Figure B8). A serious problem with this method is that the wax is primarily on the outer edges of the glass slips, and can easily be knocked off, resulting in the preparation coming apart.

John Quekett, an authority on microscopy, attributed a significant improvement on this method to professional slide-maker William Hill Darker, describing it as “Mr. Darker’s method”: “Objects, such as sections of wood, that do not require a high power for their examination, may be mounted in a very neat way after an excellent plan first practised by Mr. Darker. The following description, abridged slightly from that given in a recent work, entitled Microscopic Objects, will convey a good idea of the method to be adopted for this purpose: ‘Two slides of equal size being selected the edges of each should be bevelled off on the metal plate … so that when they are put together a groove or channel is formed ... The surfaces having been cleaned, the bevelled parts are to be coated with a thin layer of sealing-wax varnish, when this is dry, a label, if required, may be gummed to the bottom slide, and then the objects laid on it; if it be necessary to keep them in place, the smallest possible quantity of gum may be applied to one corner; the top plate is now to be laid on the specimens, one of the edges is then to be heated in the flame of a spirit lamp, and the groove filled with sealing-wax, as shown at a; when one edge is done, the others are to be heated in the same manner, until the entire groove is filled with the wax, which thus acts two purposes, one to keep the slides together, and the other to prevent the access of air. The excess of wax may be cleaned off from the edges by rubbing them upon sand-paper laid on a flat board, until they are smooth; if bright edges be required, they may be passed quickly through the flame of the spirit lamp”. The author of Microscopic Objects, from whom Quekett borrowed the description of “Mr. Darker’s Method”, was Andrew Pritchard. However, even though Pritchard was astute at self-promotion and occasional truth-stretching, he never laid claim to the invention of using wax to seal microscope slides.

In addition, Quekett’s 1852 and 1855 editions of A Practical Treatise on the Microscope, state, “Mr. Darker has long been known to microscopists for his skill in making sections of wood. From the time the achromatic microscope was first employed, he mounted sets of sections made in three different directions, between glasses, in the dry way, described in page 317 (i.e. Mr. Darker’s method). These served to illustrate the structure of the principal families of plants, and the popular as well as generic and specific names are printed on small labels, and introduced between the glasses”. This is followed by a list of common and Linnaean plant names, which correspond with known wax-sealed microscope slides of woods (Figure B9). Quekett also wrote, “The author, some years ago, was presented with a collection of sections of wood by Mr. Darker, which have not only kept in their places, but are as perfect and as free from confervae as when they were first received. They are all labelled after a very excellent plan, viz., by having the generic and specific name on one side of the label, and the popular on the other”. These comments from Quekett, and examples of such slides retailed by Pritchard (and datable by his shop addresses), indicate that Darker had been preparing slides with this method since the mid 1830s.

Figure B8.

(A) Microscope slides that were made using Charles Gould’s 1829 method of sealing slides with wax. Toward the right, a standard 1x3 inch slide of mahogany wood section prepared by "Mr. Darker’s method" is shown for size comparison.

(B) Edge view of an early wax-sealed slide, showing rough edges on the glass slips and wax protruding around the sides.

(C) Edge view of a ca. 1848 William Darker preparation, showing the beveled inner edges, filled with sealing wax, and the clean finish characteristic of "Mr. Darker’s method".

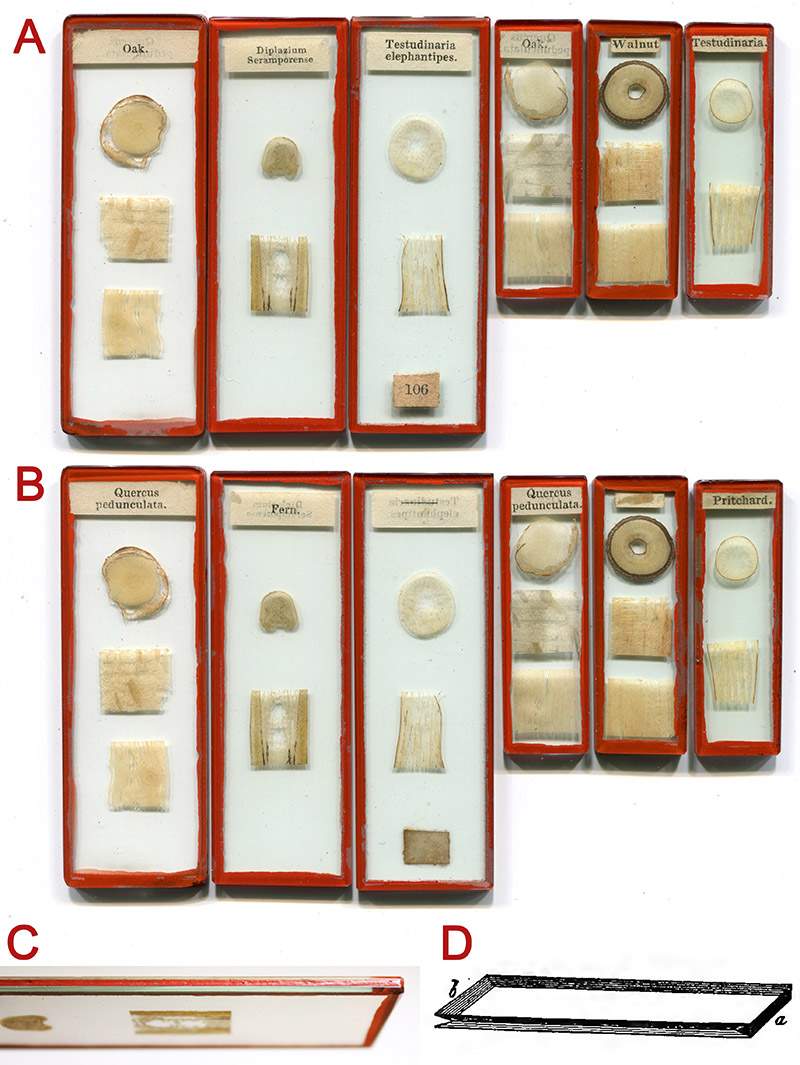

Figure B9.

(A and B) Front and back views, respectively, of microscope slides of wood sections prepared by “Mr. Darker’s method”, in both standard (1 x 3 inch) and the smaller continental size. These examples match those in Quekett’s 1852 list of Darker’s wood preparations (see Figure B10). This type of slide is occasionally found with Andrew Pritchard’s name on a piece of paper between the two glass slips, indicating retail, but not necessarily manufacture, by Pritchard.

(C) Edge view, showing the finely chamfered and polished edges and corners, and the groove where the glass slides meet, which facilitates penetration of the sealing wax for a strong bond.

(D) Figure 214 from Quekett, 1852, described as “Two slides of equal size being selected the edges of each should be bevelled off on the metal plate as represented by fig. 214, so that when they are put together a groove or channel is formed, as shown at b in the figure.” This channel for the sealing wax is the most distinctive feature of Darker’s method, resulting in a strong bond between the glass slides. Earlier slide-makers did not grind wax channels, but instead applied sealing wax to straight-edged glass slips, forming a weaker, fragile bond between the glasses.

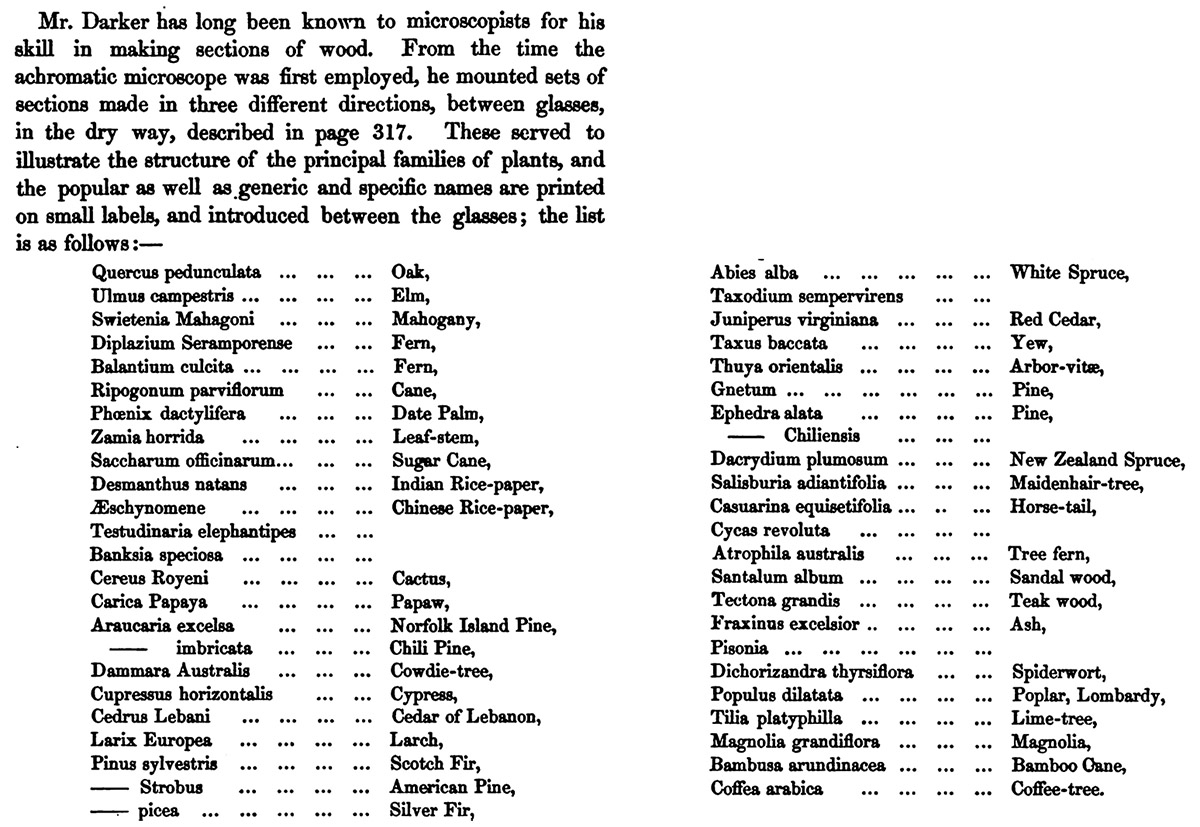

Figure B10.

List of preparations of woods produced for the microscope by William Hill Darker, from John Quekett’s 1852, second edition of A Practical Treatise on the Microscope, pages 403-405. “page 317” refers to “Mr. Darker’s method” of preparing microscope slides.

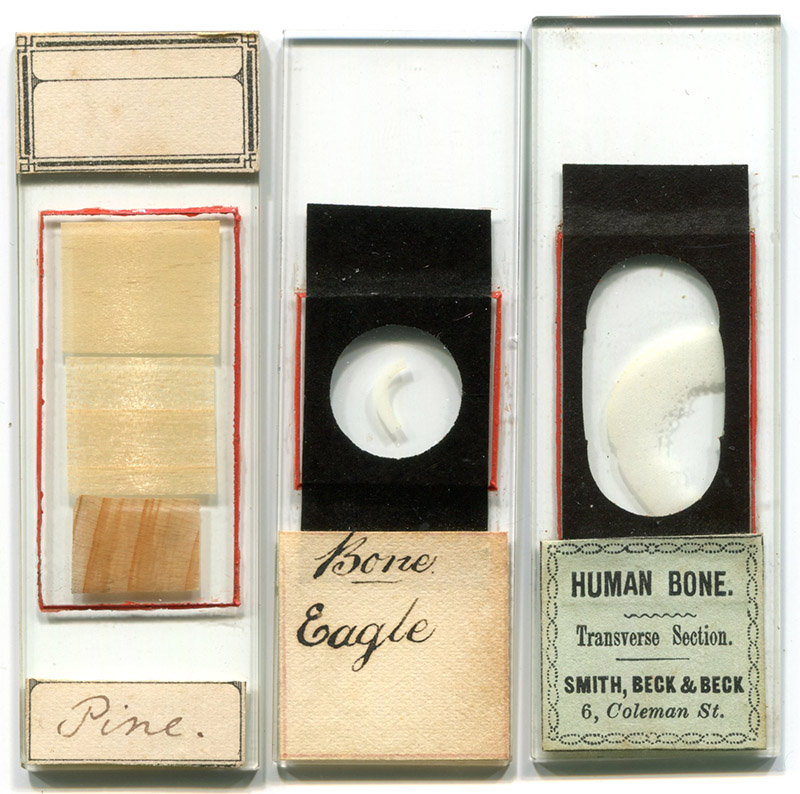

Figure B11.

Examples of small microscope slides (approximately 2 inches by 1/2 inch), prepared by “Mr. Darker’s method”, with paper inserts labeled “Pritchard”, and contained in pocket cases from Pritchard. These are identical in preparation to the larger slides by W.H. Darker, and were undoubtedly also made by him, as custom orders from Pritchard. Many such small slides do not carry Pritchard’s name, further indicating that he was not involved with production of all of these slides.

Figure B12.

Three slides that were prepared according to the method first published by Thomas Gill in 1829, and later described by Andrew Pritchard in his 1847 "Microscopic Objects": dry-mounted objects under thin cover-glass, with the edges sealed by wax. Such slides are often seen with descriptions etched into the slide by a diamond stylus. A number have black paper glued over the cover-glass, to prevent it being dislodged. Several makers, including professional mounter George Carter (1806-1870) used this method. There is absolutely no reason to assume that Andrew Pritchard was involved with either production or sale of such slides.

Figure B13.

Three microscope slides with Andrew Pritchard’s name on them, but with handwriting and/or production methods that indicate manufacture by professional slide-maker William Darker. Left to right: a dry-mounted specimen of Andrea nivalis (snow rock-moss), mounted by “Mr. Darker’s method”; finely ground sections of "fossil wood" (with Pritchard’s 1838+ address of 162 Fleet Street, and as advertised in his 1842 edition of "A List of Two Thousand Microscopic Objects" (see Figure E8, below)); elephant tusk ivory, mounted in balsam, covered with a thin cover-glass and sealed with red wax around the edges.

C. Microscope Accessories

A selection of microscope-associated items that were produced and or retailed by Andrew Pritchard.

Figure C1.

Combination live-boxes / micrometers, enabling the user to accurately determine the sizes of specimens. The three on the left bear Pritchard's 1827 - 1834/6 address of 18 Pickett Street, and the two on the right bear his 1834/6 - 1838 address of 263 Strand. Pritchard wrote of these devices in his 1832 "Microscopic Cabinet", "To render these aquatic boxes more useful, the bottom glass should have a series of lines cut on its surface, for measuring the size of the object, which in this manner is done without any additional trouble, and renders them a valuable addition to a microscope, serving the purpose both of a micrometer and objectholder. The divisions most useful are from one hundred to five hundred in an inch". Image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an internet auction site.

Figure C2.

A section-cutting machine with knife (microtome), produced circa 1835. Pritchard's name is engraved in the top surface. It was designed to cut thin slices of wood, for microscopic examination. One fits a piece of wood into the central hole, and the screw at the bottom allows incremental upward movements of the wood, which is then cut into slivers with the double-handled knife. The four holes in the top of the microtome are for fastening it to a table, for stability when cutting. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://collection.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects/co8040/early-microtome-england-1825-1835-microtome.

D. Andrew Pritchard's publications

Andrew Pritchard published a large number of books and other works on microscopy, many of which were reprinted multiple times. Through these works, he made a significant impact on microscopical investigations during the early Victorian era. While original editions of Pritchard's books are relativey expensive, electronic copies may be freely obtained from sources such as archive.org.

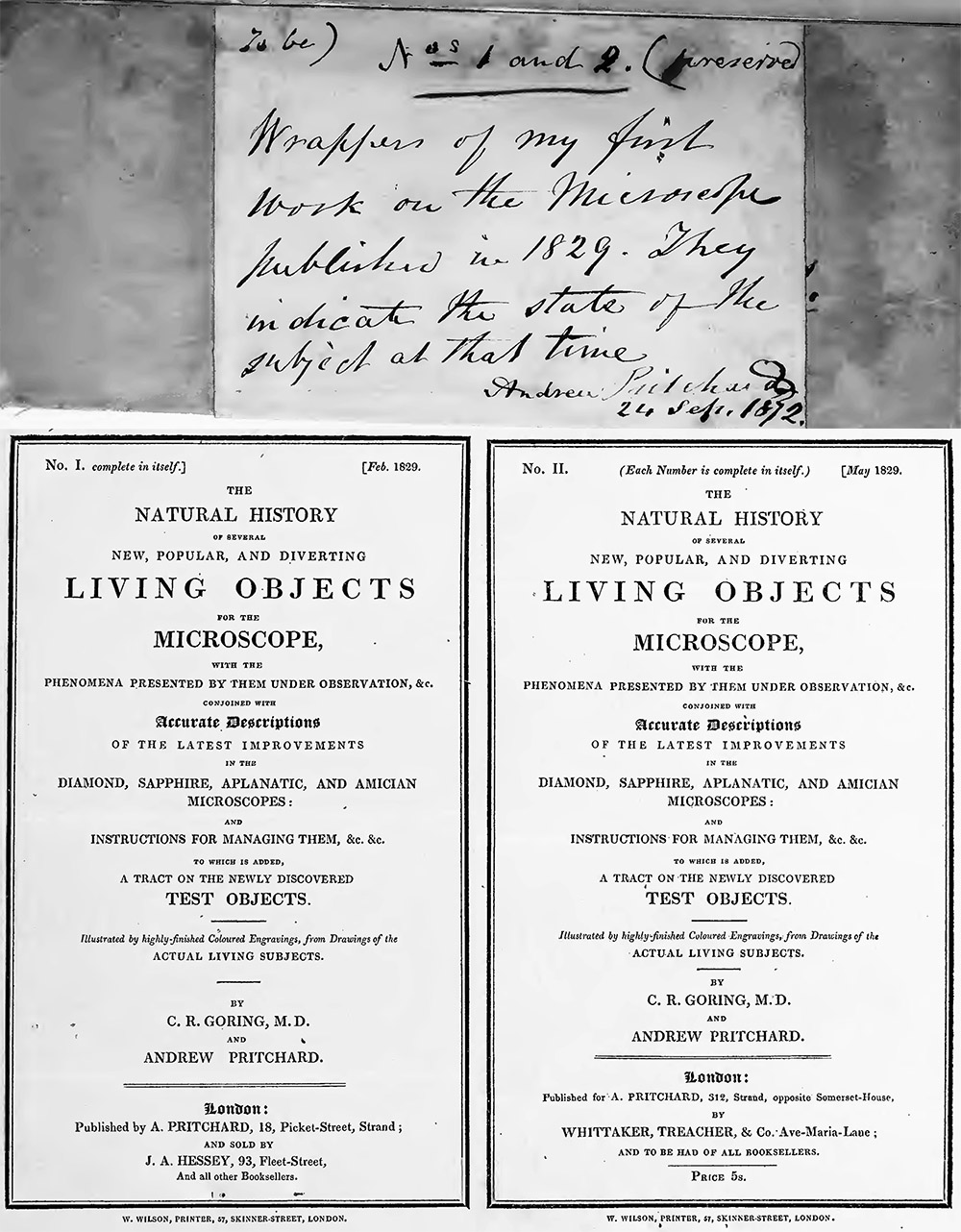

Figure D1.

Pritchard's personal copy of the 1830 edition of his "Microscopic Illustrations" includes cover pages of his first two microscopy publications, and a signed note. Pritchard changed his address from 18 Picket Street to 312 Strand between the dates of these publications, that is, between February and May, 1829. Adapted from https://archive.org/details/b21301359/page/n119/mode/2up.

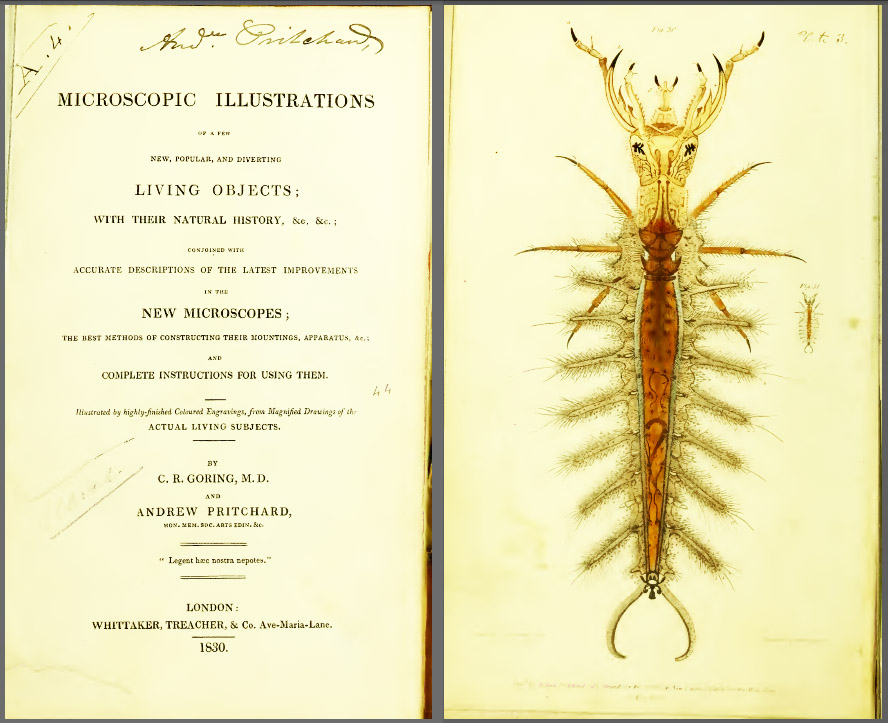

Figure D2.

Title page and frontispiece from the 1830 edition of "Microscopic Illustrations", co-written with Charles Goring (1793-1840). A second edition of this book was published in 1838, and a third edition in 1845. Adapted from https://archive.org/details/b21301359/page/n7/mode/2up.

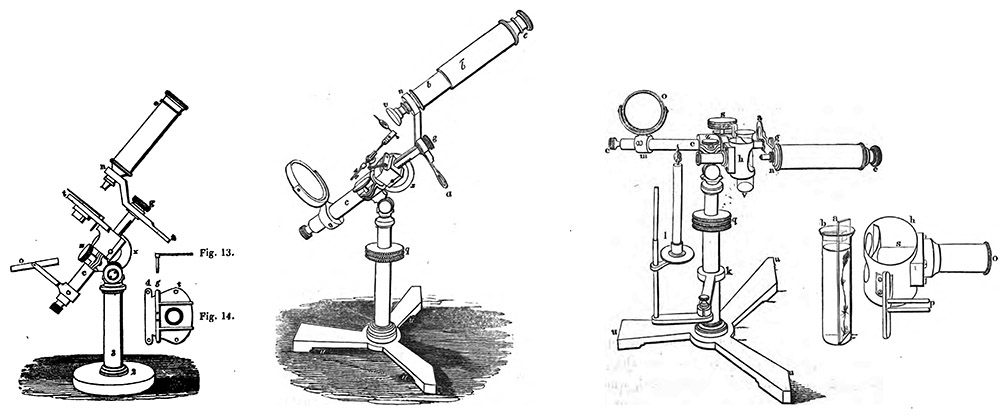

Figure D3.

Images of Pritchard's microscopes that appeared in the 1838 and 1845 editions of "Microscopic Illustrations". The left drawing is of a "Simple Achromatic Microscope" (see Figures A9 and A11, above), while the center and right drawings are of the "Standard Achromatic Microscope" (see Figures A3, A4, A5, A7, and A8, above). The drawing on the right shows an adaptation of the "Standard Achromatic Microscope", with the body tilted on its side, the stage removed, and a device installed that holds a glass tube, thereby allowing examination of specimens in water. The first, 1830 edition of "Microscopic Illustrations" did not include descriptions of these microscope styles, indicating that Pritchard began producing them between 1830 and 1838. Both the 1838 and 1845 editions also included a diagram of the Goring-designed "Operative Aplanic Engiscope" (Figure A14, above), indicating that the "Engiscope" remained in production well into the 1840s.

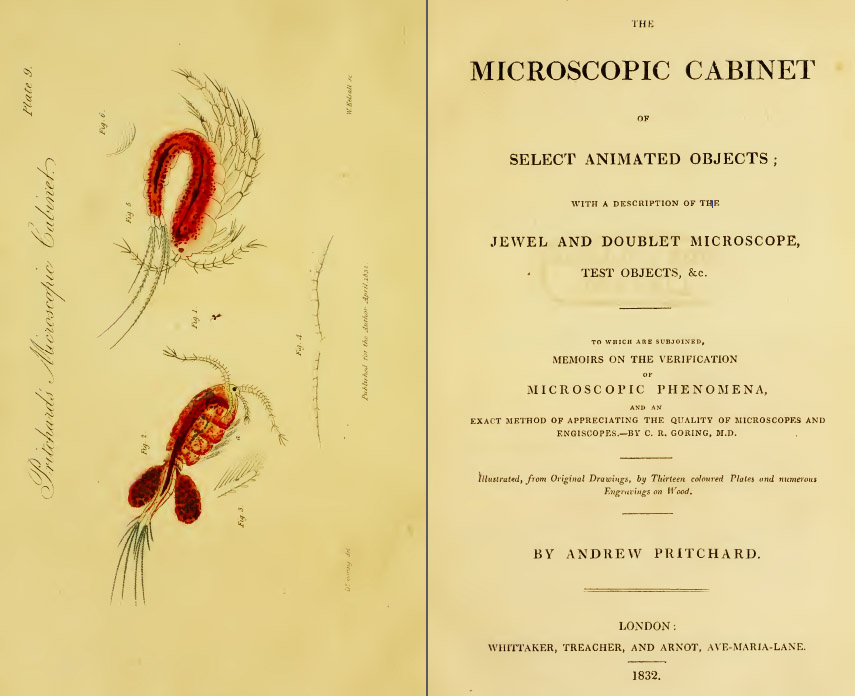

Figure D4.

Title page and frontispiece from "Microscopic Cabinet", 1832. Notably, Pritchard described a method for preserving transparent objects on glass slides, that was a predecessor of mounting in Canada balsam: "it .. becomes important to discover some method to preserve, as much as possible, their beauty, colouring, and lineament. This I have found is best accomplished by placing the object on a slip of glass, and covering it with a piece of talc, interposing a drop of a thick solution of gum and isinglass: by this means the object is prevented from drying, and when the gum has hardened is effectually preserved. In this way may be mounted all the aquatic objects described in this work, many of which cannot be preserved in any other way; they are the nearest approach to living subjects I have seen. These sliders should have a piece of paper pasted over the talc, to protect it from injury, leaving an aperture in the centre for the object, and made of an uniform size. I have caused Mr. New (i.e. professional slide-maker John New) to prepare me several sets in this way, some of which are very choice objects" (page 230).

Figure D5.

Title page of "The Natural History of Animalcules", 1834. New editions were published in 1843 and 1851.

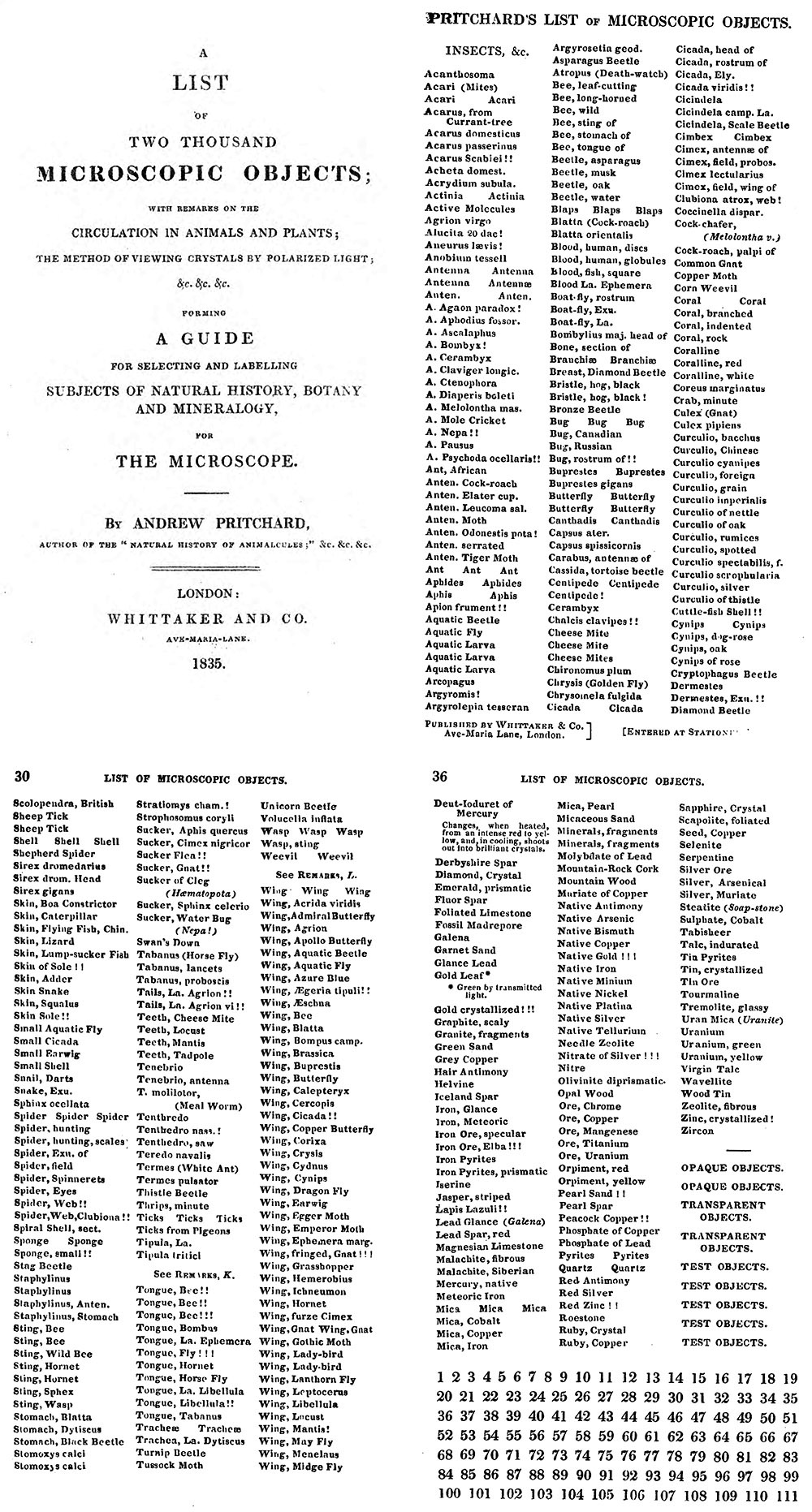

Figure D6.

Title page and three pages of specimen labels from Andrew Pritchard's 1835 edition of "A List of Two Thousand Microscopic Objects". A second, virtually identical edition was issued in 1842. The first 22 pages provided information on mounting various types of specimens, which was followed by some 30 pages of printed specimen names. The list of names were intended to be cut out by purchasers of the book: each page is printed on only one side. Pritchard employed professional slide-makers to produce slides with these same labels (see Figure B6, above), although those mounters were undoubtedly provided with loose sheets of paper from which to make labels (why would Pritchard waste books for production of slides?). Note that many of the specimen descriptions are followed by exclamation points ("!").

This book includes one of the first descriptions of using Canada balsam as a mountant, which was developed ca. 1832 by professional slide-makers John New and James W. Bond. Pritchard wrote: "There are many objects which are not sufficiently transparent to render their structure visible by transmitted light. For these, the method described in page 230 of the Microscopic Cabinet will in some cases be found useful; but the best method of mounting them, and which I have adopted with complete success, was discovered after the publication of the above work. It consists in immersing the object in Canada balsam or varnish, and pressing it between two slips of glass, so as to exclude the air-bubbles. By this treatment, many objects which otherwise possess little interest are rendered highly valuable, allowing the light to pass freely through them, exhibiting their structure, and presenting to the admiring spectator the most brilliant and superb colours. By this method also, many cylindrical bodies are rendered perfectly distinct, the diffraction at the edges being in a great degree destroyed by the refractive power of the medium".

Figure D7.

Title page of "Micrographia", 1837. This is a collection of essays on microscope theory and applications.

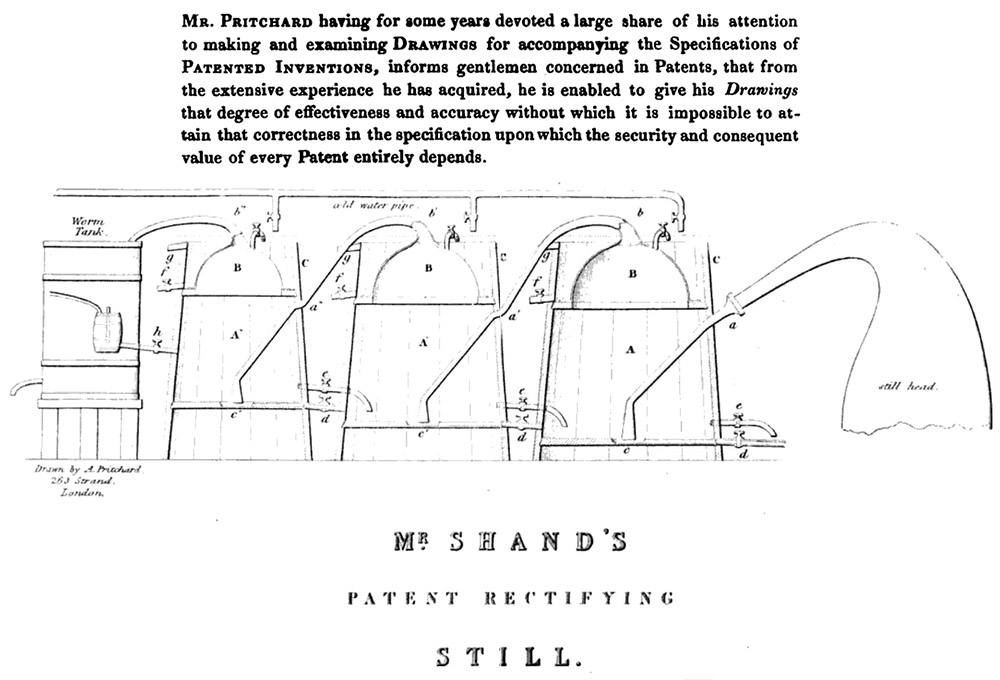

Figure D8.

Andrew Pritchard took comissions to draw patented designs and other devices - the upper paragraph was printed opposite the Table of Centents in his 1830 "Microscopic Illustrations". His drawing of "Mr. Shand's Patent Rectifying Still" was published in "The Quarterly Journal of Agriculture", 1837.

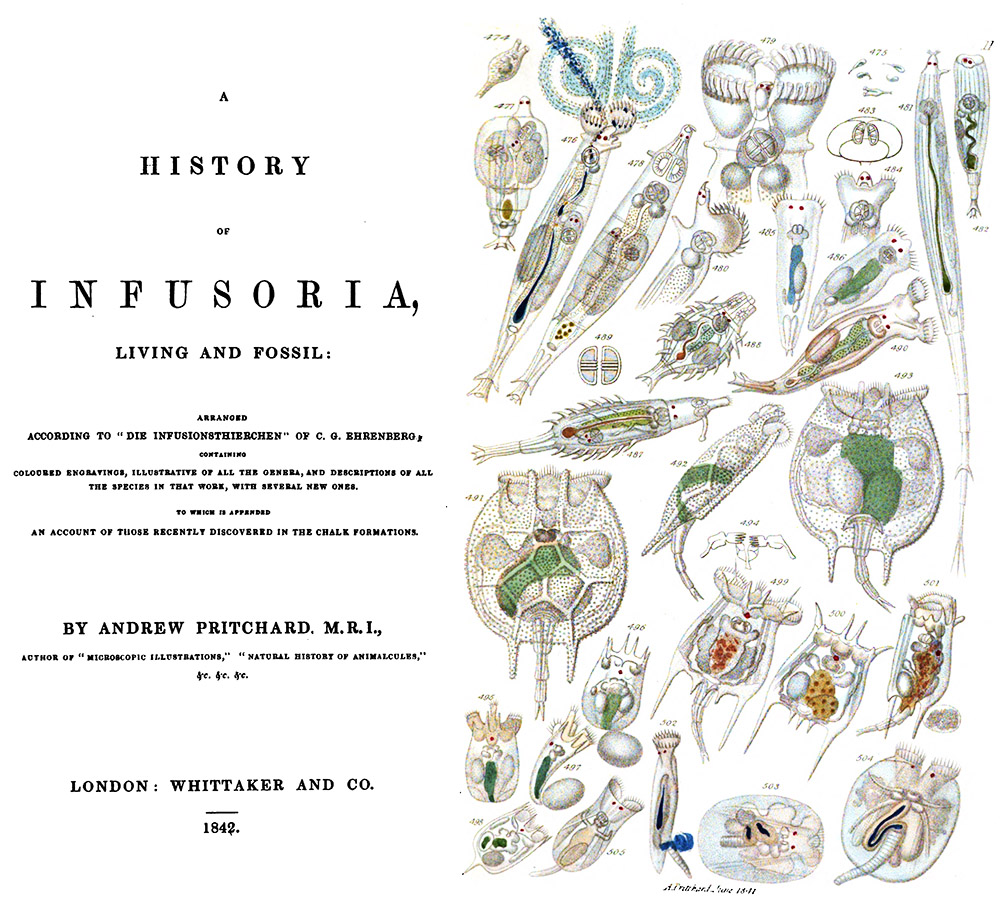

Figure D9.

The title page and a hand-colored plate from Pritchard's 1842 "A Natural History of Infusoria, Living and Fossil". New editions were published in 1849, 1852, and 1861.

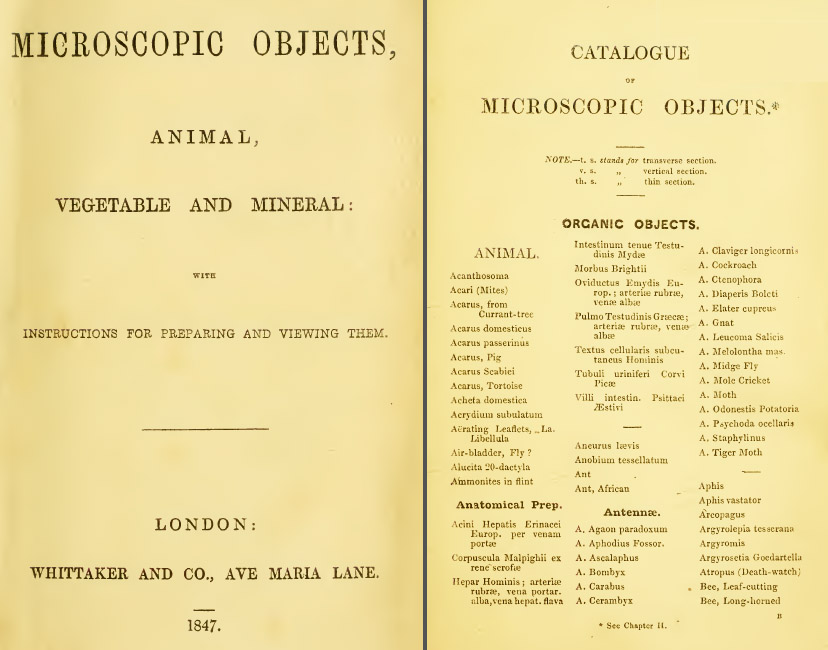

Figure D10.

Title page and a page of specimen labels from "Microscopic Objects", 1847. It is fundamentally similar to the earlier "A List of Two Thousand Microscopic Objects", with printed specimen labels and instructions for mounting specimens.

A striking feature of this book is that it does not give the name of its author, although numerous references throughout make it obvious that it was written by Andrew Pritchard. As a consequence of not listing himself as the author, Pritchard repeatedly pats himself on the back without appearing to be overly self-praising.

One especially eggregious piece of self-promotion appears on page 133: "On Mounting Microscopic Objects in Canada Balsam - We are indebted to Mr. Pritchard for the suggestion of this superb mode of embalming". He then cites his 1832 "Microscopic Cabinet", which actually described mounting of objects in a mixture of gum arabic and isinglass (see Figure D5, above). A brief description of mounting in Canada balsam was published in Pritchard's 1835 "A List of Two Thousand Microscopic Objects", which is reproduced almost verbatim in "Microscopic Objects". However, the writings of James Bowerbank and other contemporaries make it clear that Canada balsam was developed as a mountant circa 1832 by professional slide-makers John New and James W. Bond, following leads from chemist John Cooper.

"Microscopic Objects" also includes a description of dry-mounting objects between two glass slips, and sealing the edges with wax (pages 145-147) (see Figures B9 and B11, above). Pritchard's description included cutting bevels on the inner edges of the glass slips, into which the wax flows to form a tight bond and which provides protection against the wax being knocked off during handling. As noted above, John Quekett attributed this method to professional slide-maker William Hill Darker, calling it "Mr. Darker's method". Although such slides have come to be known as "Pritchard's slides", due to his name occasionally being on such slides, it is notable that Pritchard did not take credit for the method.

This book includes a second mounting method that has also become assocated with Pritchard's name (page 147) (see Figure B12, above). Pritchard wrote, "This plan .. enables you to employ very thin plates for covering the object ; but it is more liable to injury. The lower plate should be of thin plate glass about 1/10th of an inch thick, the edges carefully squared ; the upper plate may be as thin as required ; it must be cut about 1/16th of an inch shorter and narrower than the lower one. After the object has been arranged upon the lower plate, the upper one is to be placed over it in such a manner as to leave a uniform margin around the lower plate. By this means a rectangular groove is formed, which is to be filled with sealing-wax. As the upper plate is usually thin, the best and strongest cement for this purpose is japanner's gold size thickened with a little vermilion, or when that colour is not desirable, lamp-black". This method was not novel to Pritchard, but dates back to at least 1829, when it was described by Thomas Gill in his "Technological Repository".

Figure D11.

Andrew Pritchard's 1847 "Microscopic Objects" included a page that could be cut out to make paper slide covers. In the illustrated example, an owner began to prepare these slide papers, by cutting holes for specimens, but evidently thought better of the project. Loose sheets of this slide paper were available for purchase. William Notcutt wrote in 1859 that "a very neat figured paper may be purchased of Mr. Pritchard, 162, Fleet Street, being an engine-turned gold pattern on dark purple paper, designed especially for slides, and with blank spaces for punching out".

Figure D12.

The title page of Pritchard's 1847 "English Patents: Being a Register of All Those Granted for Inventions in the Arts, Manufactures, Chemistry, Agriculture, etc. etc., During the First Forty-Five Years of the Present Century".

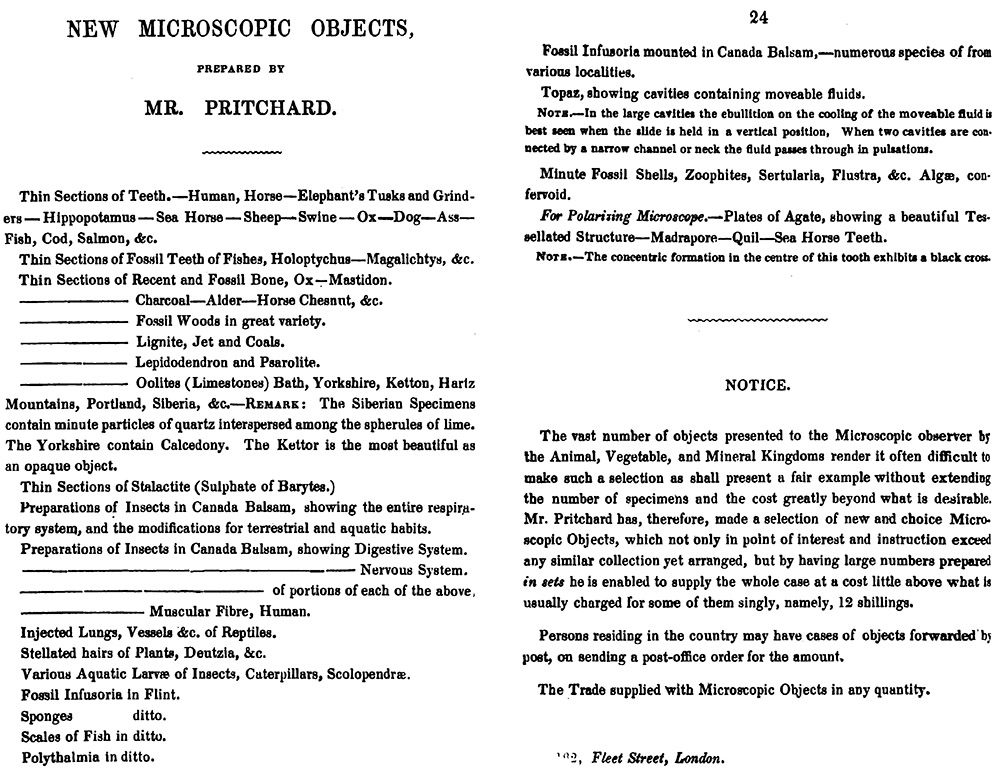

E. Catalogues, Price Lists, and Advertisements

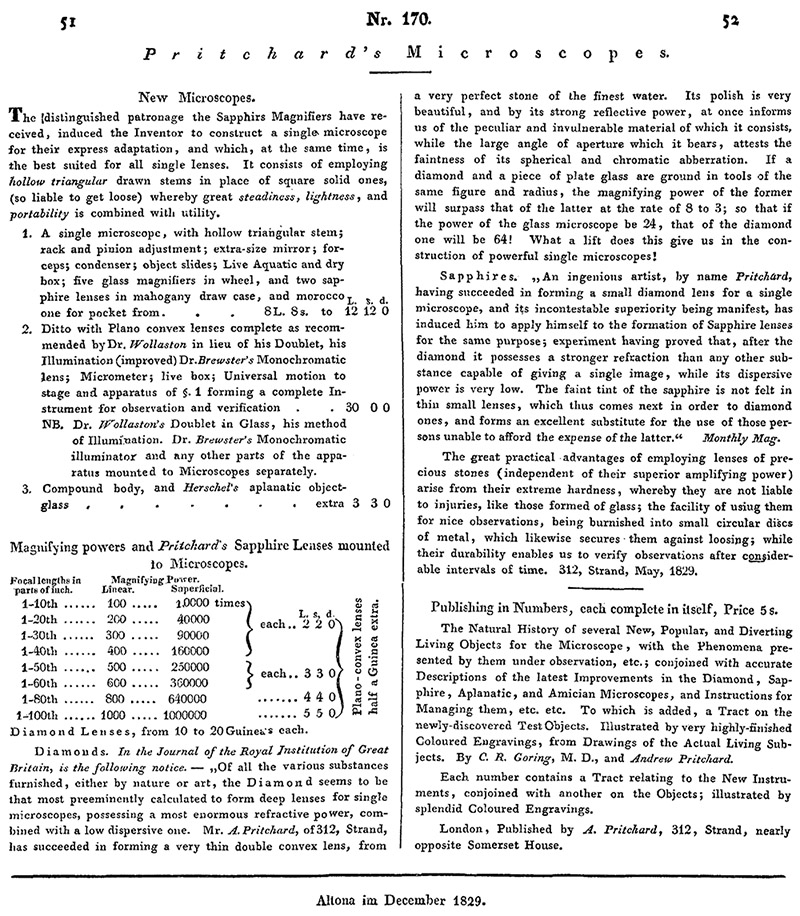

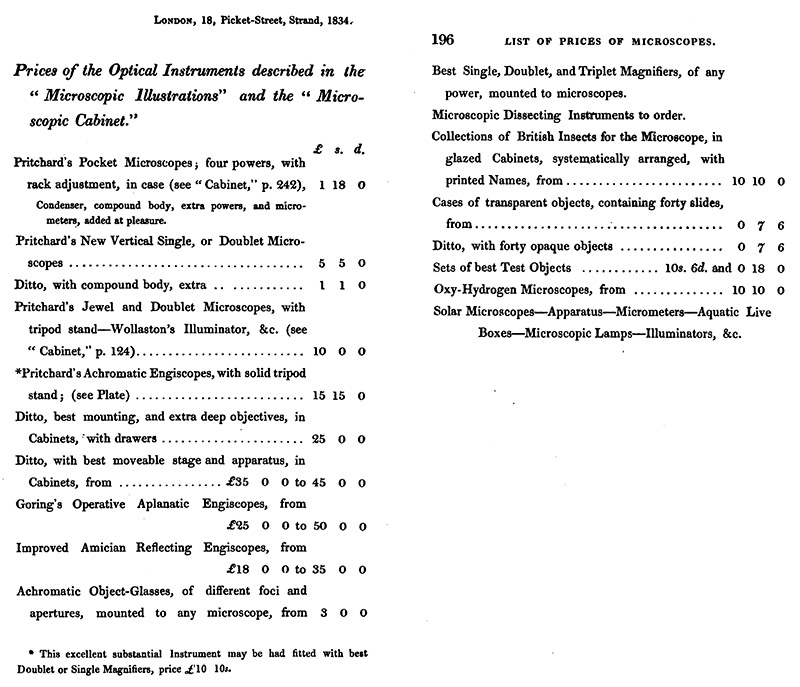

Figure E1.

An 1829 price list from the December issue of "Astronomische Nachrichten".

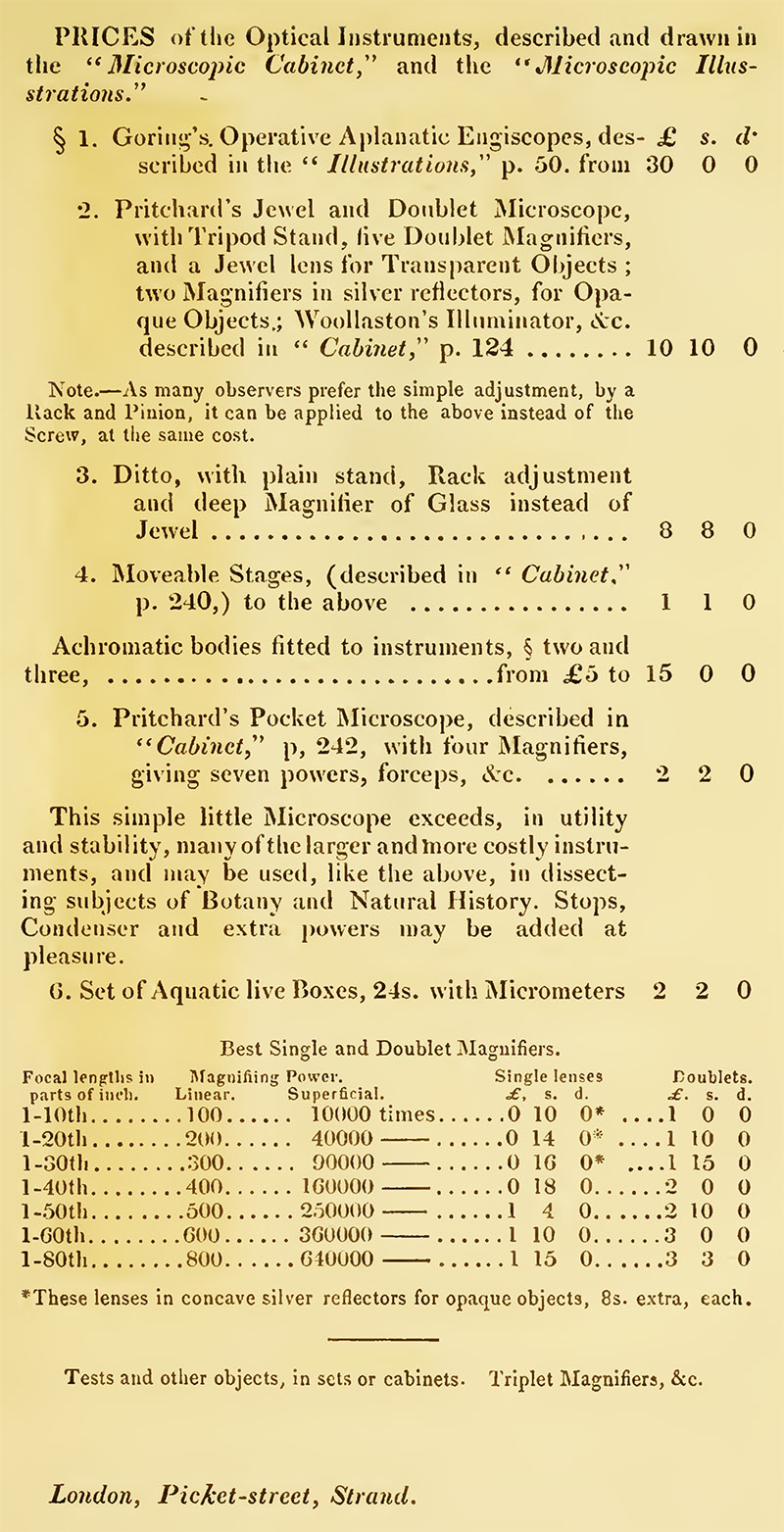

Figure E2.

Price list from the 1832 edition of "Microscopic Cabinet".

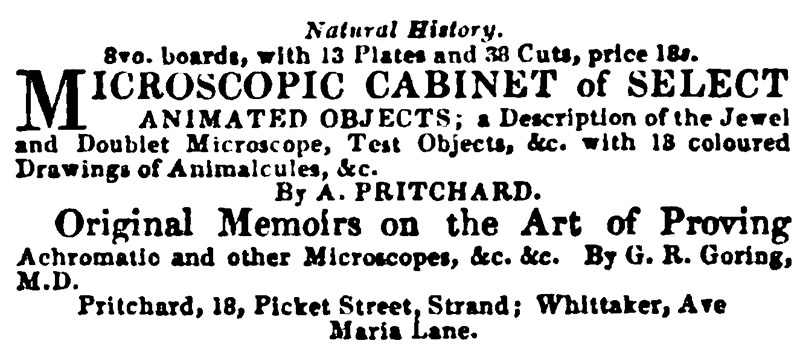

Figure E3.

1832 advertisement from "The Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences".

Figure E4.

Price list from the 1834 edition of "The Natural History of Animalcules".

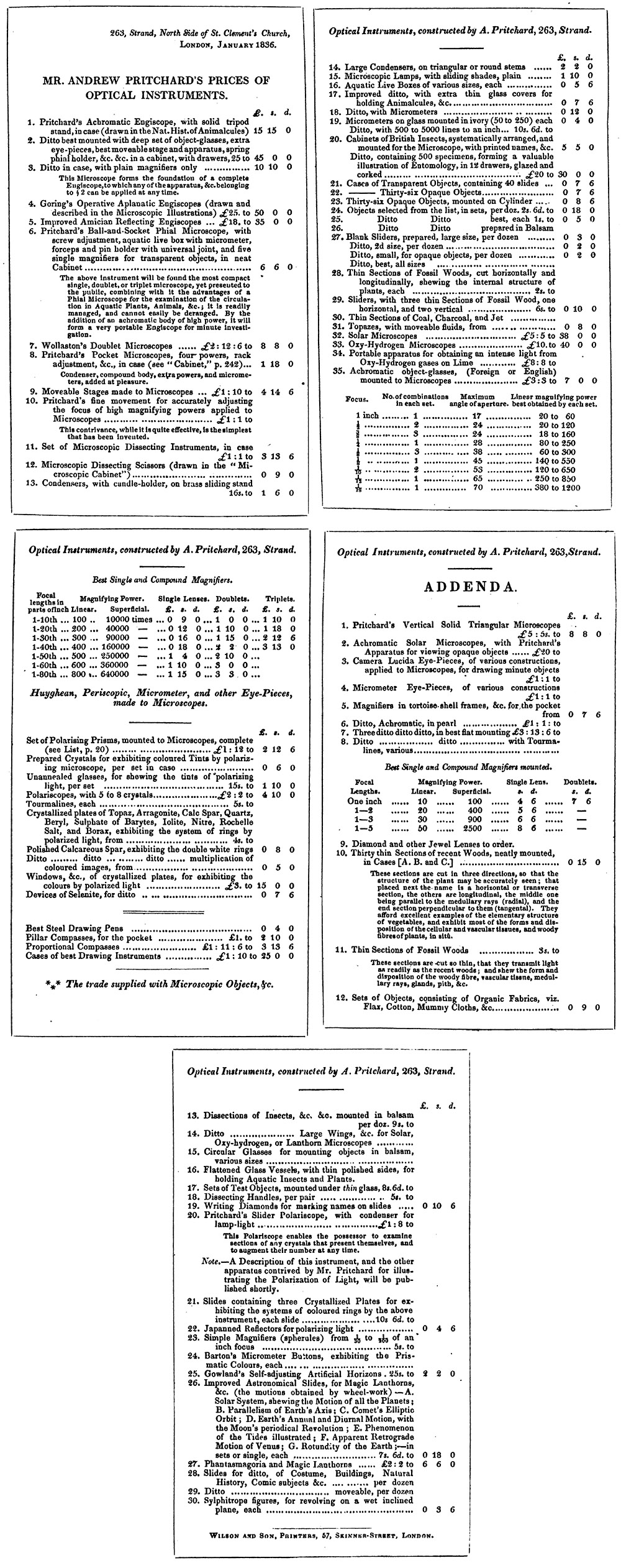

Figure E5.

An 1836 catalogue, published in "The Quarterly Review".

Figure E6.

1839 price list, from "The Annals and Magazine of Natural History".

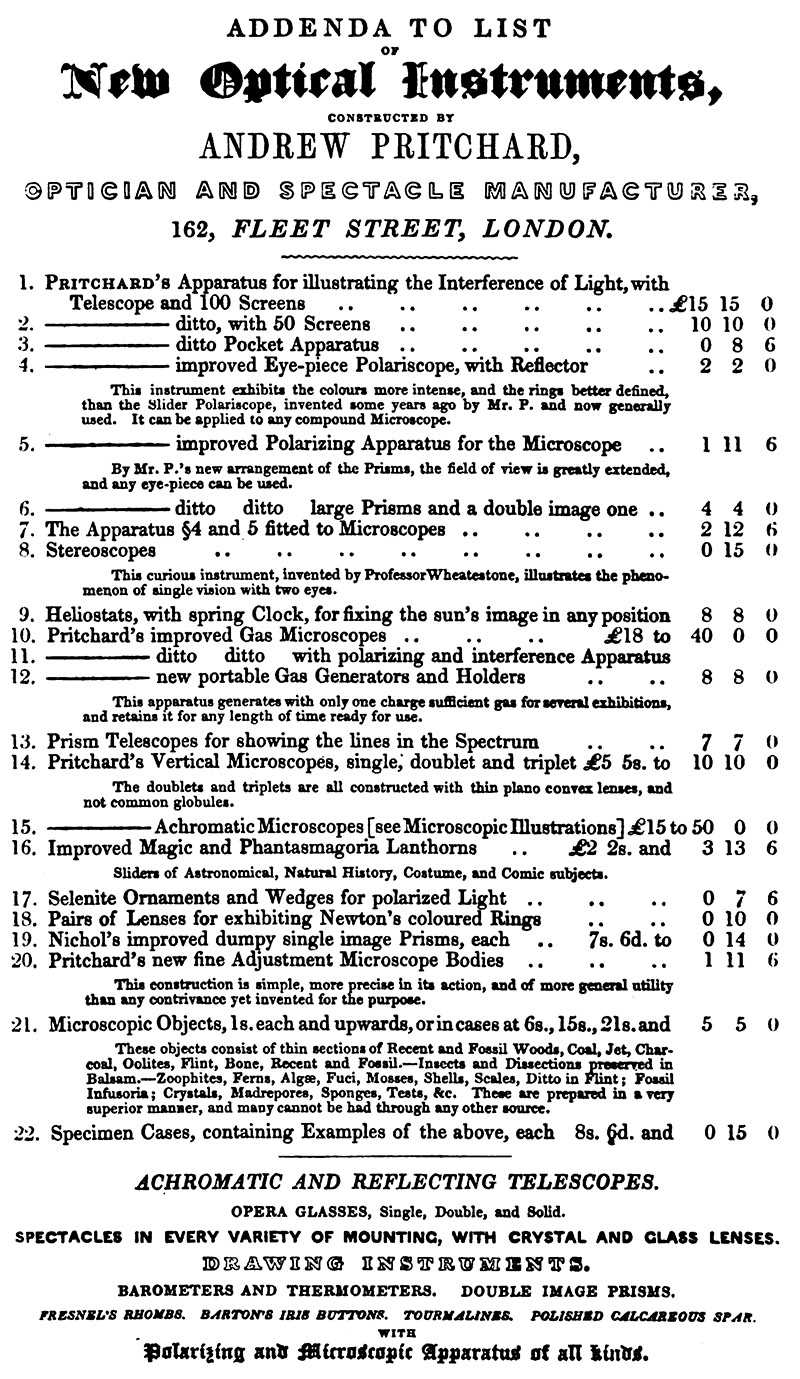

Figure E7.

A catalogue that was bound into Pritchard's 1842 edition of "A List of Two Thousand Microscopic Objects".

Figure E8.

Pritchard's 1842 edition of "A List of Two Thousand Microscopic Objects" also included a list of "New Microscopic Objects prepared by Mr. Pritchard". As with other slides that Pritchard sold, it is unlikely that he prepared these himself, but instead employed professional slide-makers such as William Darker and Charles M. Topping (e.g. Figure B13, above).

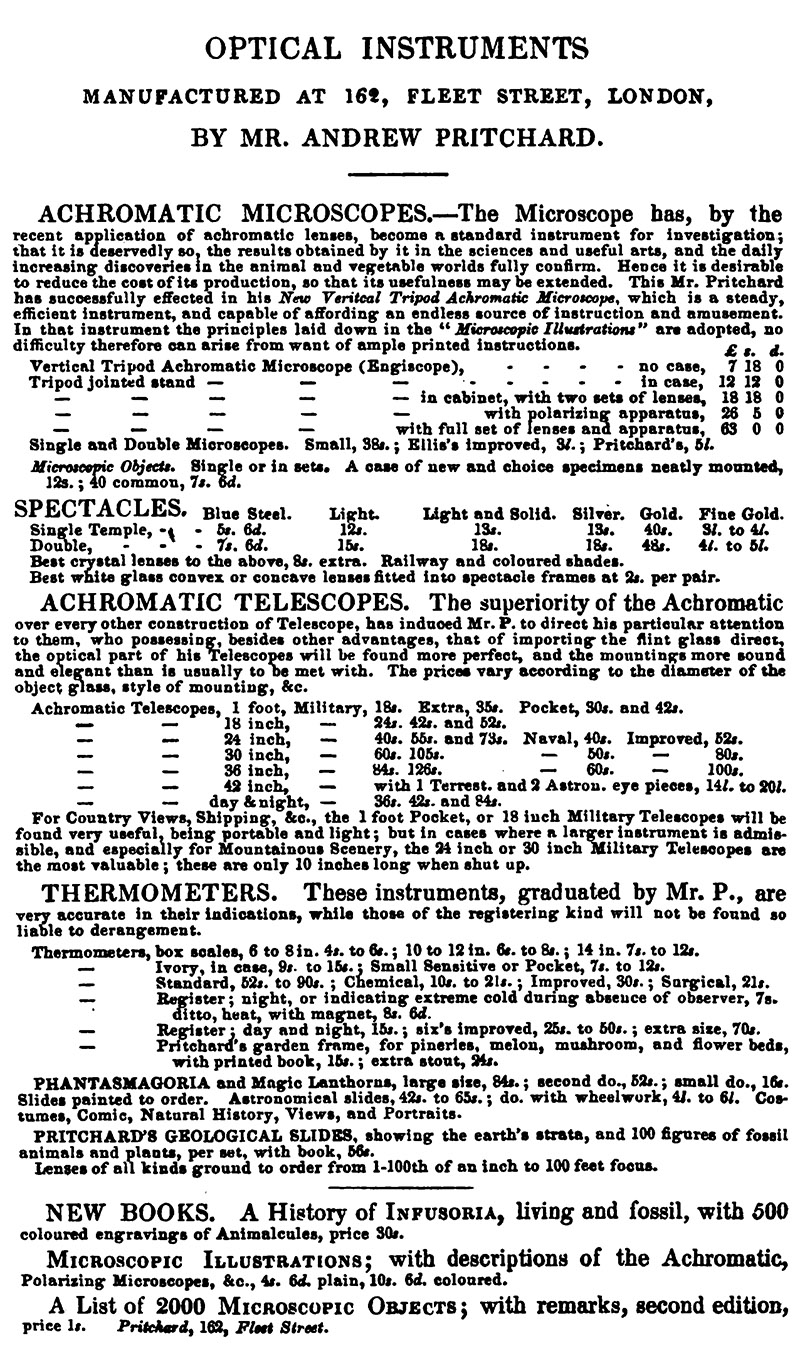

Figure E9.

An 1849 price list, from the second edition of "A Natural History of Infusoria, Living and Fossil".

Figure E10.

Pritchard's brother-in-law, Samuel Lawrence Straker (ca. 1813 - 1889), took over management of the shop in 1849. This advertisement appeared in the October 6, 1849 issue of "The Lancet".

Figure E11.

Samuel Straker left Pritchard ca. 1855-1856, to established his own business. This advertisement was published in the December 6, 1856 edition of "The Athenaeum". According to Nuttall (2006), Pritchard continued to operate his shop at 162 Fleet Street on a part-time basis until 1858.

F. On the life of Andrew Pritchard

Pritchard's obituary from Nature, 1882:

"We regret to announce the death, on November 24, of Mr. Andrew Pritchard, M.R.I., F.R.S. Edin., &c., of Highbury, London, whose name will be best remembered in connection with several improvements of the microscope, the use of "test objects," and as being the author of "A History of Infusoria," the fourth edition of which, enlarged to nearly 1000 pages, was published in 1861.

Born in London in December, 1804, he was almost entirely brought up by his grandfather, one of the chief cashiers in the Bank of England. On the foundation of the Mechanics' Institution in Southampton Buildings, by Dr. Birkbeck, Mr. Pritchard entered as a student. The microscope was then a very imperfect instrument, and Mr. Pritchard worked hard at the achromatisation of lenses, and was the first to propose to take advantage of the high refracting power of the diamond, ruby, and sapphire for the manufacture of single lenses, these giving good definition without the coloured borders incidental to ordinary flint glass. Between the years 1829 and 1837 he published several works on the microscope, in which he was aided by Dr. Goring, particularly the "Microscopic Illustrations," "Micrographia," and the "Microscopic Cabinet," for which several good plates were prepared.

In the year 1836 Mr. Pritchard was elected a Member of the Royal Institution, being proposed by Faraday, and in the previous year joined the British Association at Dublin, taking part in the deliberations of this body until comparatively recent times. In 1873 the Royal Society of Edinburgh conferred upon him their fellowship, in recognition of his scientific attainments, as evidenced by his great work, the "History of Infusoria," a memorial of patient industry and biological research".

Pritchard's entry in The Dictionary of National Biography:

"Pritchard, Andrew (1804-1882), microscopist, eldest son of John Pritchard of Hackney, and his wife Ann, daughter of John Fleetwood, was born in London on 14 Dec. 1804. He was educated at St. Saviour's grammar school, Southwark, and was afterwards apprenticed to his cousin, Cornelius Varley, a patent agent and brother to John Varley, the artist. On the expiration of his apprenticeship he started in business as an optician, first at 18 Picket Street, then at 312 Strand, and afterwards at 162 Fleet Street. He retired from business about 1852, and died at Highbury on 24 Nov. 1882. He married, on 16 July 1829, Caroline Isabella Straker.

Brought up with the "independents", Pritchard later in life associated with, though he never actually became a member of, the sect known as Sandemanians, and it was in connection with that body he first made the acquaintance of Faraday. He finally became a unitarian, and in 1840 joined the congregation at Newington Green, a connection which lasted throughout his life. He was greatly interested in all the institutions connected therewith, and was treasurer of the chapel from 1850 to 1872.

Pritchard early turned his attention to microscopy, and in 1824, while still with Varley, he, at the instigation of Dr. C.R. Goring, endeavoured to fashion a single lens out of a diamond. Despite the discouragement of diamond-cutters, he ultimately succeeded in 1826. He also fashioned simple lenses of sapphire and of ruby. His practical work on the microscope, however, was less productive of lasting results than his literary labours on the application of the instrument to the investigation of microorganisms. His "History of the Infusoria" was long a standard work, and the impetus it gave to the study of biological science cannot be readily overestimated".

Figure F1.

Andrew Pritchard, circa 1855. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from an image in the Natural History Museum, London.

Figure F2.

Andrew Prichard, from a photograph dated June, 1869. Adapted from an internet auction site for nonprofit, educational purposes.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Howard Lynk, Joe Zeligs, Barry Sobel, Allen Wissner, and Jurriaan de Groot for their contributions to this and many other stories of early microscopists.

Resources

The Annals and Magazine of Natural History (1839) Price list from Andrew Pritchard, Vol. 4, October issue

Bowerbank, J.S. (1870) Reminiscences of the early times of the achromatic microscope, The Monthly Microscopical Journal, 3:281-285

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 77 and 108, plate 2Davidson, B. (2009) John New and the introduction of Canada balsam into slide-making, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, 41:95-108

The Dictionary of National Biography (1896) Pritchard, Andrew, pages 402-403

Falcon-Lang, H.J., D.M. Digrius (2014) Palaeobotany under the microscope: history of the invention and widespread adoption of the petrographic thin section technique, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, 42:253-280

Gill, Thomas (1829) On expeditiously mounting transparent objects for viewing with lenses of highly magnifying powers, Gill's Technological Repository, Vol. 3, pages 194-196

Gill, Thomas (1829) On the editor's facile mode of mounting small transparent objects for the microscope, Gill's Technological Repository, Vol. 5, pages 4-5

Goring, C.R., and A. Pritchard (1830) Microscopic Illustrations, Whittaker, Treacher, and Co., London

Goring, C.R., and A. Pritchard (1833) Microscopic Illustrations, Whittaker, Treacher, and Arnot, London (reprint of 1830 edition)

Goring, C.R., and A. Pritchard (1837) Micrographia, Whittaker and Co., London

Goring, C.R., and A. Pritchard (1840) Microscopic Illustrations, Second edition, Whittaker and Co., London (reprint of 1838 edition)

Gould, C. (1829) The Companion to the Microscope, 6th edition, W. Cary, London

The Lancet (1849) Advertisement from Andrew Pritchard and Samuel Straker, October 6 issue, advertiser section

The Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences (1832) Advertisement from Andrew Pritchard, May 5 issue, page 288

Morrison-Low, A.D. (2005) Andrew Pritchard Bicentenary Meeting Natural History Museum, London, 14 December, 2004, Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society, pages 20-21

Nature (1882) Obituary of Andrew Pritchard, Vol. 27, page 113

Notcutt, William L. (1859) A Handbook of the Microscope and Microscopic Objects, E. Lumley, London, pages 7 and 30-31

Nuttall, R.H. (1977) Andrew Pritchard, optician and microscope maker, The Microscope, Vol. 25, pages 65-81

Nuttall, R.H. (1979) Andrew Pritchard’s contribution to Metallurgical microscopy, Technology and Culture, Vol. 20, pages 569-577

Nuttall, R.H. (2006) Marketing the achromatic microscope: Andrew Pritchard’s engiscope, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 40, pages 309-330

Pritchard, A. (1825) On an improved cement, for holding small lenses, whilst grinding and polishing them. The Technical Repository, Vol. 7, page 303

Pritchard, A. (1832) The Microscopic Cabinet, Whittaker, Treacher, and Arnot, London

Pritchard, A., and C.R. Goring (1845) Microscopic Illustrations, Third edition, Whittaker and Co., London

Pritchard, A. (1842) A Natural History of Infusoria, Living and Fossil, Whittaker and Co., London

Pritchard, A. (1842 and many other years) English Patents: Being a Register of all Those Granted for Inventions in the Arts, Manufactures, Chemistry, Agriculture, &c., Whittaker, London

Pritchard, A. (1847) Microscopic Objects, Whittaker and Co., London

Pritchard, A. (1847) English Patents: Being a Register of All Those Granted for Inventions in the Arts, Manufactures, Chemistry, Agriculture, etc. etc., During the First Forty-Five Years of the Present Century, Whittaker and Co., London

Pritchard, A. (1849) A Natural History of Infusoria, Living and Fossil, Whittaker and Co., London

Pritchard, A. (1852) A Natural History of Infusoria, Living and Fossil, Whittaker and Co., London

Pritchard, A. (1861) A Natural History of Infusoria, Living and Fossil, Whittaker and Co., London

The Quarterly Journal of Agriculture (1837) Patent rectifying still, pages 68-76

The Quarterly Review (1836) Catalogue and price list from Andrew Pritchard

Quekett, J. (1852) Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope, Second edition, H. Balliere, London

Quekett, J. (1855) Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope, Third edition, H. Balliere, London

Stevenson, B., and H. Lynk (2016) William Hill Darker, the Scientists’ Engineer, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 42, pages 559-579