Thaddeus Stevens Up de Graff, 1839 - 1885

by Brian Stevenson and George E. Blackham

last updated October, 2017

Thad S. Up de Graff was an American surgeon and microscope enthusiast. He served for several years as a Vice President of the American Society of Microscopists, and, in 1882, was elected Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society.

His microscope slides have a very professional quality (Figure 1). Although records of advertisements have yet to be located, it is highly likely that Up de Graff produced slides for commercial distribution.

Figure 1.

Microscope slides by T.S. Up de Graff. The undated slide of blood cells from the horned toad (a name given to several species of lizard, of the genus Phrynosoma, that live in the southwestern USA) may date from ca. 1883, when Up de Graff testified as an expert witness in a murder trial that he could discriminate human from dog blood. This claim raised concern among many other microscopists, so Up de Graff may have made this and similar slides to illustrate differences among animal blood cells.

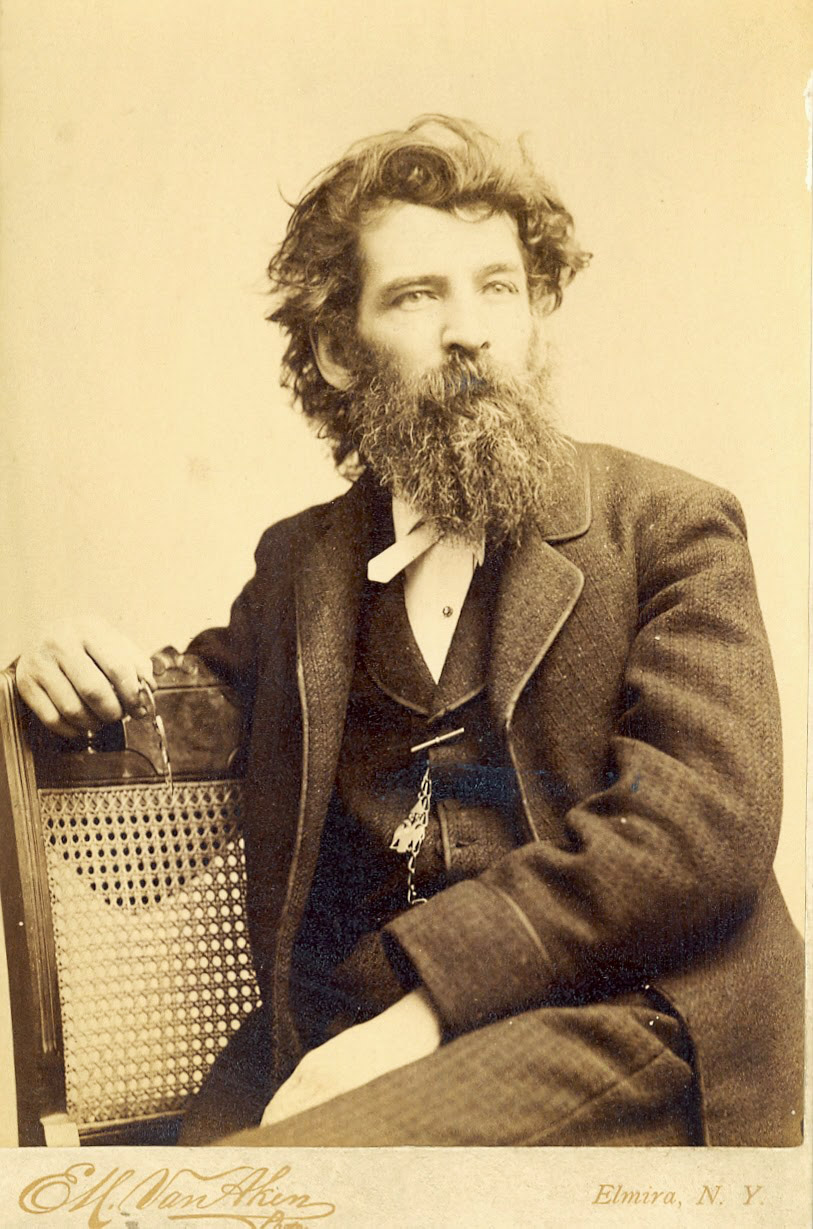

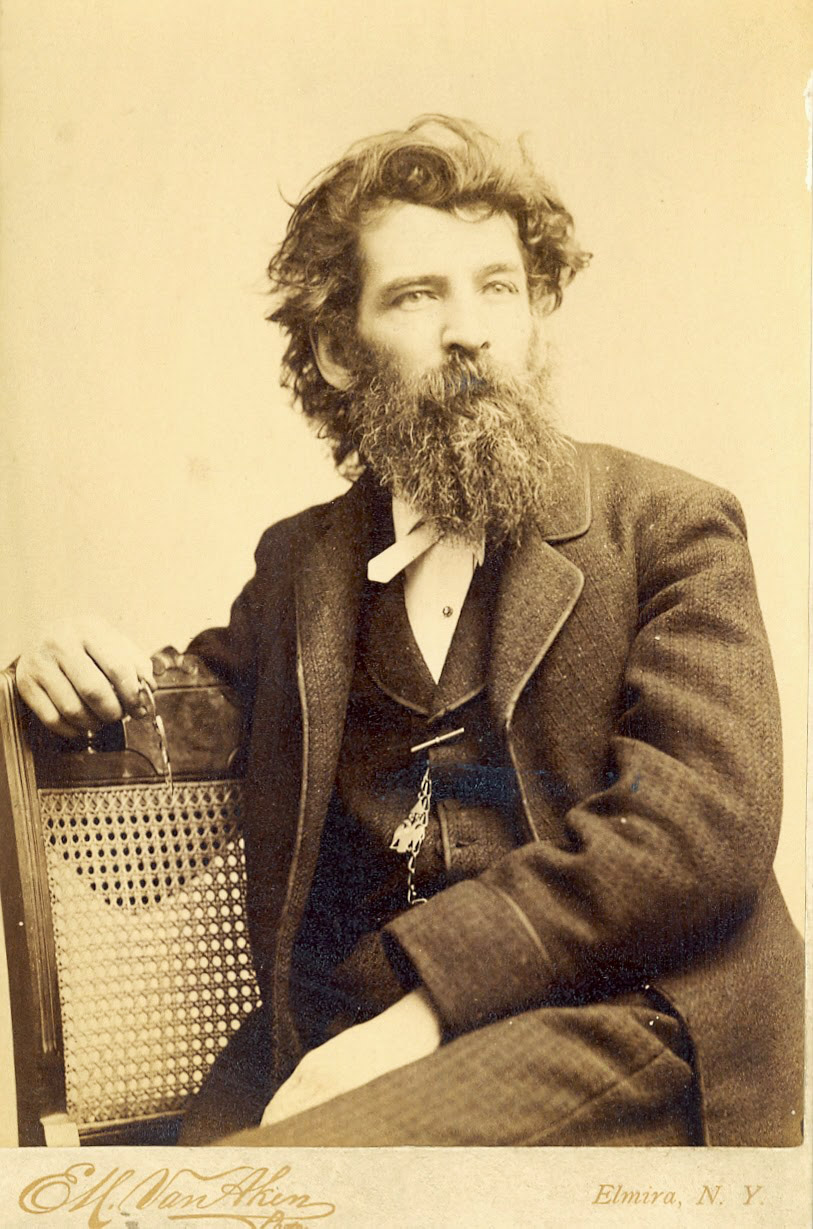

Figure 2.

An undated photograph of Thaddeus Up de Graff. Adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://chemungcountyhistoricalsociety.blogspot.com/2014/05/csi-elmira.html/

Following the death of Up de Graff, his colleague at the American Society of Microscopists, George Blackham, wrote a lengthy memoriam. It contains substantial, first-hand information on Up de Graff’s life, and is quoted extensively below.

Blackham: “Thad Stevens Up de Graff was born in Harrisburg, (Pennsylvania), April 12, 1839. His father was a distinguished surgeon of eccentric habits and great mechanical genius, but unfortunately a slave to the opium habit. From him the subject of this memoir inherited his genius and an extremely sensitive, nervous organization; and from his mother, who is still living, a slender and delicate, yet powerful frame.

While a lad he attended Dr. Fisher's Seminary, at Selin's Grove, and afterward spent five years in the study of medicine, receiving his diploma from the St. Louis (Missouri), Medical College in 1859; he also pursued a special course in chemistry and mineralogy at the University of Michigan. He has, at rare intervals, told me a little of the struggles and trials of his youth; how he did menial service during his attendance at medical college to get board and lodging; how, after his graduation, he went on the railroad as far as his money would take him, and brought up in an Indiana town, moneyless, friendless and unknown; how fortune smiled on him, success attended his practice, and money began to come in; and how, best of all, he wooed and won Miss Ella A. Hale, of Indianapolis, and married her on the 1st day of December, 1859 - ‘and lived happy ever after’, as the old stories put it.

Shortly before the War of the Rebellion (i.e., the U.S. Civil War, 1861-1865) broke out, he moved to Olney, Illinois. He was a war democrat, and chanced to be at the house of the democratic candidate for Governor of Illinois when that gentleman received the news of his nomination, and, at his request, the Doctor introduced him to the crowd who came to serenade him on the occasion. This made the Doctor somewhat well known as a democrat, and, when it became necessary for speakers to go into Southern Illinois to strive to awaken Union sentiments, the Doctor was selected as one of them, for the climate of that section (Egypt, as it was called) was not, at that time, healthy for republicans. So well did he succeed that not only were his Union sentiments tolerated, but he awakened the latent patriotism of many of his hearers and a company of volunteers was raised and he was elected Captain. Assigned to the Twenty-sixth Regiment of Illinois Volunteers, Captain Up de Graff and his company took part in many battles. He was wounded at the battle of Mill Spring, Kentucky, and was afterwards obliged to resign on account of ill health. When he recovered sufficiently, he resumed the practice of his profession in Vincennes, Indiana, and shortly after moved to Elmira, N.Y.

Here his genial manner soon won him friends and his skill brought him patients, and his offices in the Rathbun block were enlarged from time to time till they were very complete. Unfortunately they were completely destroyed by fire and with them a remarkable collection of surgical instruments and appliances - many of them of his own invention - together with valuable cabinets of anatomical, pathological and other specimens, and many of the records of his practice. The offices were rebuilt and refitted, but soon proved too small, and in 1873 he moved across the river and opened the Elmira Surgical Institute - a private hospital where most of his subsequent work was done. He has often spoken to me of this as one of the wisest steps of his life; the more complete control and supervision which he was thus enabled to exercise over his patients while under treatment being, in his opinion, a most important factor in his success. This hospital was usually full to overflowing; but few save himself and his beneficiaries knew how many of the deserving poor received there not only skillful treatment, but board and lodging gratis, till they were able to go upon their way rejoicing. No one could ever guess by his manner at clinic hour which were the pay-patients and which the ones to whom all was free.

His specialty was surgery, and more particularly that of the eye and ear, - he had operated for cataract over six hundred times. Here, the delicacy of his touch, his remarkable finger skill and his surgical courage served him well, and he usually operated for cataract without anesthesia and without the use of the fixation forceps. He was also remarkably skillful and successful in general surgery, having operated for ovariotomy twenty-two times, tied the common carotid and common iliac arteries, made several successful amputations at the thigh, and, indeed, made most if not all of the major operations, besides innumerable smaller ones.

His mechanical genius often led him to the invention of new forms of surgical instruments, - sometimes valuable improvements for general use, often skillful modifications of existing instruments to adapt them to some peculiar case, - but all exhibiting that neatness of design and execution which characterized all his work”.

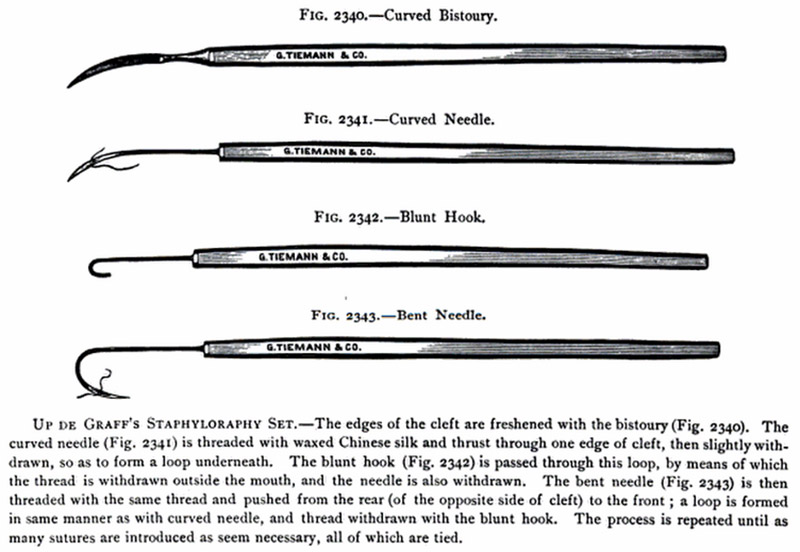

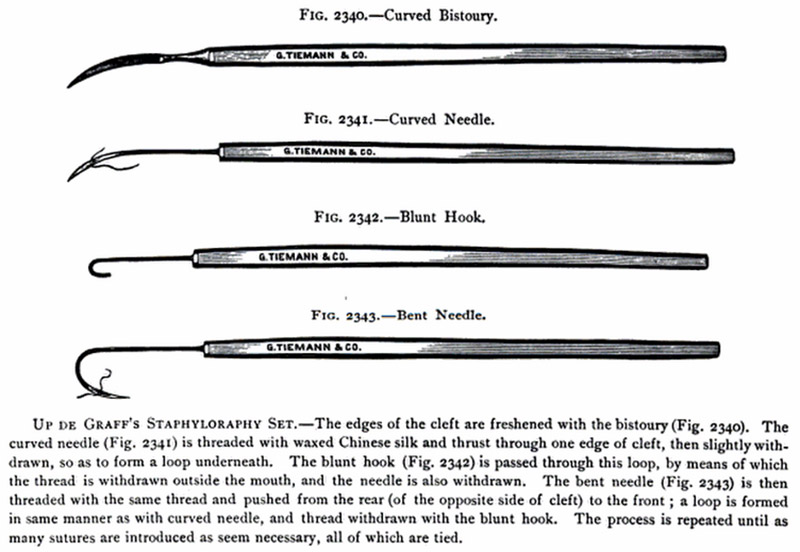

Figure 3.

A set of surgical tools that was designed by T.S. Up de Graff, and retailed by the G. Tiemann Company.

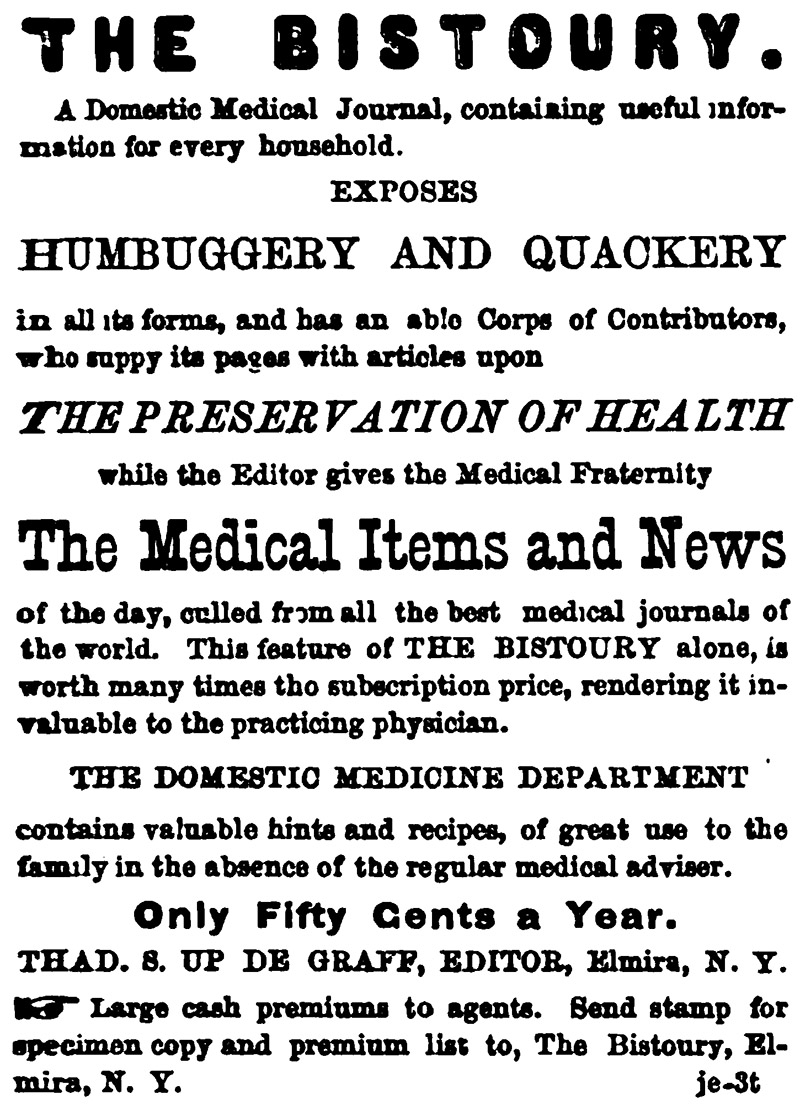

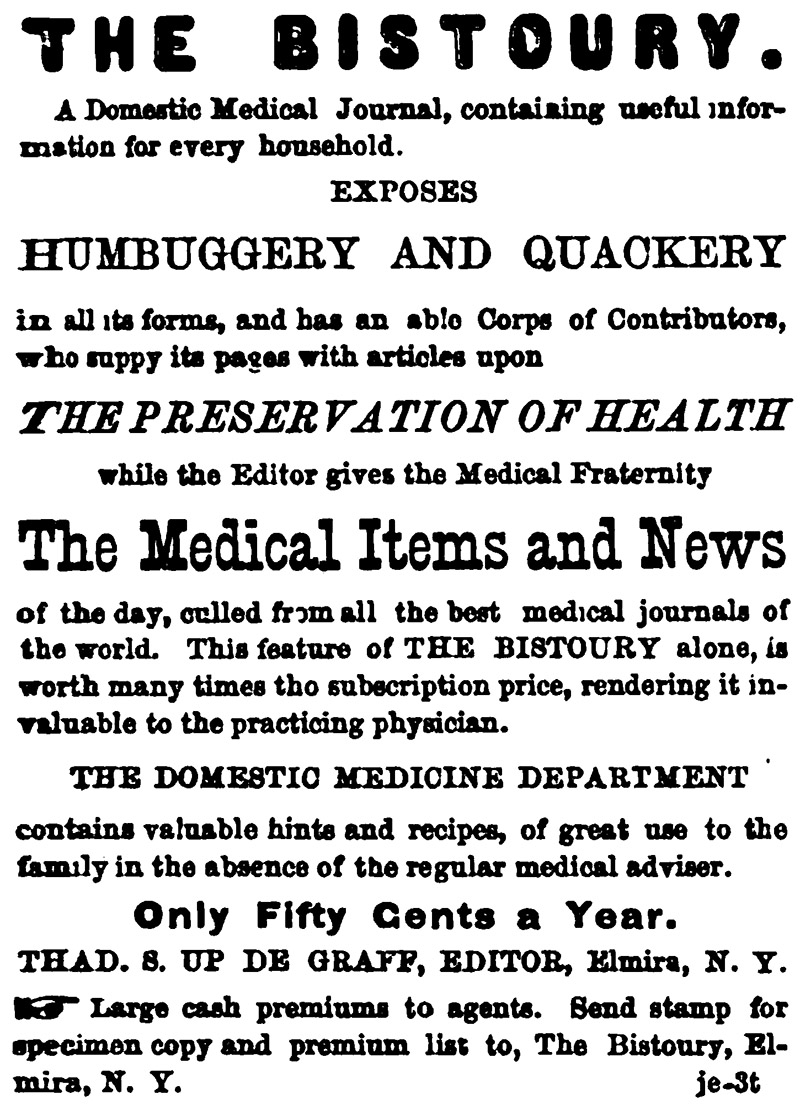

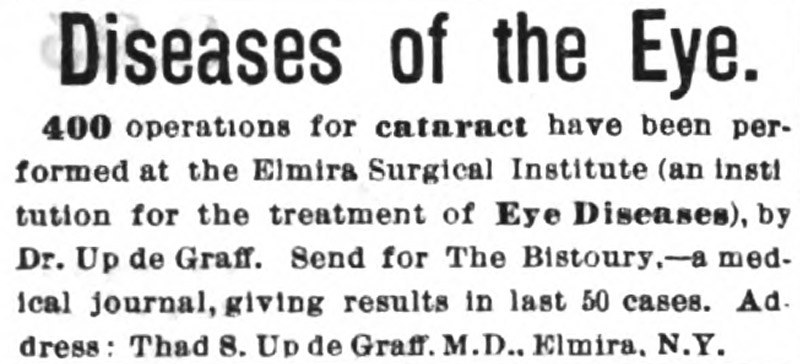

Stevenson: Up de Graff’s business in Elmira flourished, in part due to his unorthodox practice of advertising. From 1865 through 1885, he published a newsletter, The Bistoury, that was a combination of information on medical news and advertisements for his own surgical business (Figure 4). The numbers of Up de Graff’s operations that were cited by Blackham undoubtedly came from Up de Graff’s publications. An 1878 advertisement by Up de Graff is shown in Figure 5. In 1867, The Medical and Surgical Reporter complained, “we find that Dr. T.S. Up De Graff does render himself obnoxious to criticism, and places himself outside of the ranks of the regular profession by his violation of the ethical rules of the profession. He publishes for gratuitous distribution a monthly paper entitled ‘The Bistoury’, in which he advertises himself to the public as a surgeon, setting forth his successful operations in a way that is entirely incompatible with a regular standing in the medical profession. In this paper is an announcement in flaming capitals, that he will be in Selin's Grove, Pa., on certain specified days, to perform such surgical operations as may be presented. The announcement is very much in the style of the poster before referred to - all the apparent difference being that one is posted up at public places to be read, while the other is handed around gratuitously. This course cannot be defended. It is resorting to the arts and tricks of the charlatan, and he who is guilty of it voluntarily places himself outside the pale of the profession, and has no claim to recognition as a physician or surgeon in regular standing. Furthermore, it is entirely irregular, and contrary to our code of ethics, for any one who wishes to maintain a regular standing in the profession to recognize professionally, or hold intercourse with one who resorts to such expedients to advertise himself to the public. If Dr. Up De Graff has abilities as a surgeon, why should he not abandon these irregular practices, and trust to his own merits and the goodwill of the profession, to establish him in the section of country in which he resides? If, however, he chooses to persist in the course he has been pursuing, he must not blame us for placing him among charlatans, and he must not expect those who desire to maintain a standing in the profession to exchange professional courtesies with him in any way”.

Figure 4.

An 1873 advertisement for Up de Graff’s newsletter, ‘The Bistoury’

Figure 5.

An 1878 advertisement, touting Up de Graff’s skill as an eye surgeon. Advertising by medical practitioners in the U.S.A. was severely frowned upon until late in the twentieth century.

Blackham: “I first became acquainted with Doctor Up de Graff in 1879, through the agency of our mutual friend Dr. S.O. Gleason. I shall never forget the impression he made upon me. I had called on Dr. Gleason, whom I knew through correspondence on matters microscopical, and he suggested to me that we both go over the river and see Dr. Up de Graff, as he also was interested in the microscope.

When we stopped in front of the Elmira Surgical Institute, a remarkable-looking little man came out to meet us. He was not, I think, more than five feet five or six inches high, slender, but lithe and agile in body, with a rather large, finely-shaped head set firmly on his sloping shoulders, long straight black hair combed back from a high white forehead and falling well down on the neck; bright, piercing eyes deeply set under the overhanging brows - a large aquiline nose, delicately-cut, sensitive mouth, partly hidden by the flowing moustache, and the lower part of the face entirely hidden by a long, pointed dark beard. He wore an ordinary business suit, except the coat which he had replaced with his laboratory jacket of velvet. I noted the extreme delicacy of his hands, the bright clearness of his voice and manner, and the cordiality with which he received me as if I had been an old friend. We went directly into his private office and began to talk microscope at once. He had just received about a dozen objectives of some inferior foreign make sent him by some New York optician for examination. I was asked my opinion and gave it, softening it a little, and so was led to air my then unpopular heresy in reference to lenses of wide aperture. We stayed to tea and I enjoyed the visit immensely. After a time I visited Elmira again and called on Dr. Up de Graff, and he insisted on my staying to tea, wanted me to stay all night, ‘Why not spend a week with me?’ Next time I saw him I was on sick leave; was going to New York for medical advice, and stopped over in Elmira to see a sister who was teaching there. I went to the Institute to call on Dr. Up de Graff, intending to continue my journey the same night, but this he would not hear of; I must stay all night and get rested. It finally resulted in my staying three weeks, enjoying the doctor's hospitality, receiving the benefit of his skill, and becoming acquainted with his charming family; and from that day till the present I have been more like a member of that family than a stranger. The family then consisted of the doctor and his charming wife, his eldest son Thad, then a student of medicine and now his father's worthy successor ; a second boy, Way, about sixteen, I think, rather sedate and a born surgeon; Fritz, the youngest boy - boy all over - and two dear little girls, Kate and Alice, the latter, the baby of the family, very pretty and very affectionate, was so suggestive of a nice little white kitten that she was generally known as ‘Puss’; there was also a young lady niece of Mrs. Up de Graff's, Miss Gibbs.

Into this family I was received on familiar terms. I was equally welcomed into the doctor's laboratory, his operating room, his private office, and into the parlor and nursery of his residence. Thus I had opportunity to see him in all aspects, as an investigator, as a surgeon, as a father, and as a friend. And it is something for me to be able to say now, that having seen him thus frequently and intimately, I can recall no word or deed of his that standing by his grave I would care to blot out. Naturally quick-tempered and impulsive, the warmth of his affections kept his temper from becoming unpleasant. Hospitable and generous to a fault, fond of good living and good company, he delighted to see his table filled with the good things of the earth and surrounded by friends.

He was, I think, the most versatile man I ever knew. He seemed able to do anything he chose to undertake, and to do it well. As an operator upon the eye he was most dextrous - as the fact that he usually operated for cataract without anesthesia and without fixation is sufficient to prove, - as a general surgeon his practice was characterized by a bold prudence and a degree of mechanical skill in planning and executing difficult operations seldom equalled. He took up oil-painting for a pastime, once, and soon got beyond the range of ordinary amateur work; he was a good carpenter, as many bits of work about his Institute remain to prove; an enthusiastic flyfisher, it was his custom to spend a month of each year on the banks of the Lycoming in his favorite pursuit, and in communion with Nature. He embodied the results of his experience in camp in a book called ‘Bodines’, full of wit, humor, natural history and shrewd philosophy. I have seen the original manuscript as sent to publishers, and it is most beautifully and legibly written, on commercial note paper, without scratch or blot, and I am not surprised that the publishers stated that they had never seen such a MS. before and never expected to see such another. He was an excellent amateur photographer, both with the ordinary camera and with the microscope”.

Stevenson: Up de Graff was an avid fisherman and outdoorsman. In 1879, he published a book on fishing and camping at a favorite site in Pennsylvania, Bodines: Or, Camping on the Lycoming. It ran a second edition in 1883. It is still referred to as a classic of outdoors life.

Figure 6.

An illustration from Up de Graff’s ‘Bodines”. The author is shown in the foreground, with a fishing net.

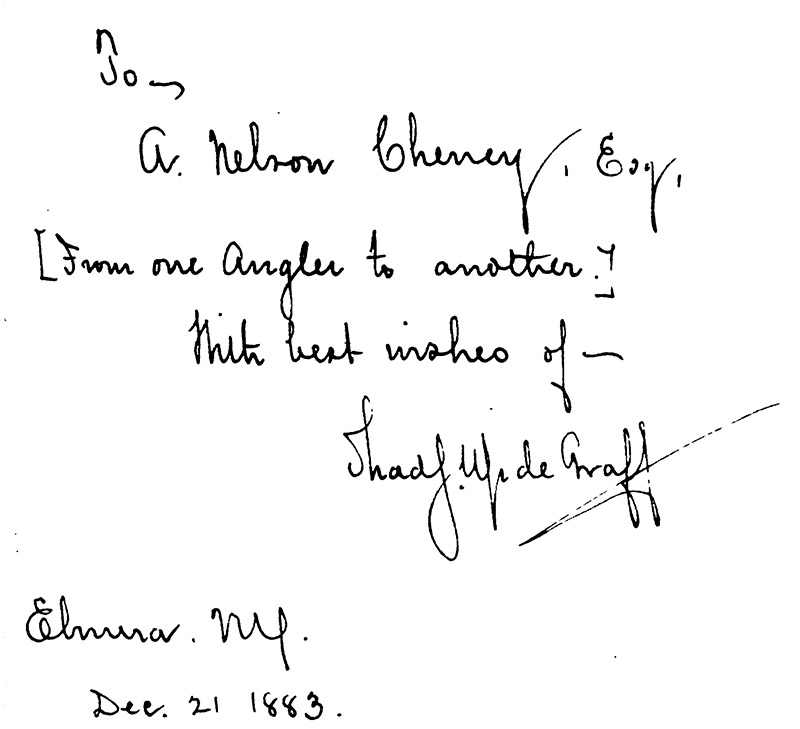

Figure 7.

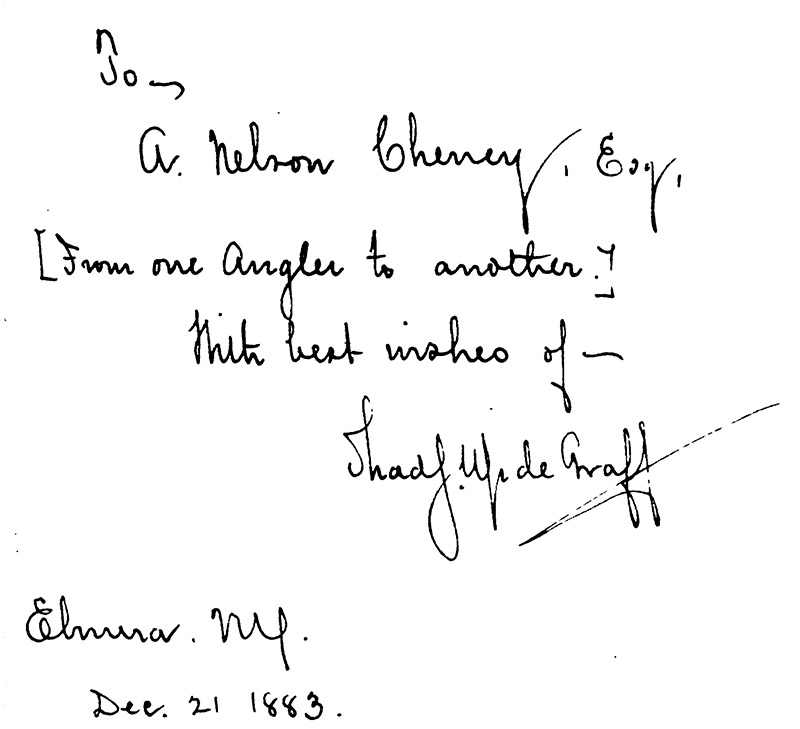

Inscription and autograph by T.S. Up de Graff. From the copy once owned by A. Nelson Cheney, which is available at google.com.

Blackham: “In preparing and mounting microscopical specimens he had few, if any, superiors in this country or, of course, elsewhere; he was possessed of great executive ability, and was the life of the Elmira Microscopical Society; and it was due largely to his exertions and abilities as chairman of the local committee that the Elmira meeting of the A.S.M. became the success it was, and the turning-point in the history of this organization. As our worthy Treasurer, Prof. Fell, truly stated, ‘The A.S.M., at Columbus, was in a fair way to fulfill the predictions of its enemies till Drs. Gleason and Up de Graff appeared on the scene and extended their hearty invitation to go to Elmira’. I was elected President, and Dr. Up de Graff one of the Vice-Presidents, and, though I worked hard and was ably assisted by Profs. Kellicott and Fell as Secretary and Treasurer, I doubt that success would have crowned our efforts but for the work done by Dr. Up de Graff. He secured the splendid Park Church for our meetings, got prominent citizens to throw open their doors and receive our members as their guests, secured the attendance of prominent microscopists, who knew little of our young society and came only on his urgent invitation. He looked after every detail, kept the sub-committees up to their work, and contributed, I honestly believe, more than any other one person to the success of that meeting, upon which the existence of this Society depended”.

Stevenson: On May 10, 1882, Up de Graff was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Microscopy, a significant recognition of his contributions to microscopy, “The following were elected Ordinary Fellows:– Messrs. T.S. Up de Graff, M.D., John Inglis, J.P., Captain A.H. Southey, Prof. Ramsay Wright, and John Wright”.

During that same year, Up de Graff claimed to have resolved the eighteenth band of Charles Fasoldt's engraved plate. This was a component of a series of engraved lines that were extremely close together, and would require a very fine set of microscope lines to discriminate as individual lines. Their claim led to the questioning of Fasoldt’s engraving capabilities, as well as the qualities of Up de Graff’s microscope. The American Monthly Microscopical Journal wrote, “Some gentlemen in Elmira have been amusing themselves by resolving ruled plates. Drs. Gleason and Up de Graff have resolved the eighteenth band of Fasoldt's plate, which is said to have 120,000 lines to the inch. Dr. Gleason has stated this so positively that we cannot doubt the resolution of that band, but before we are convinced that lines as close as 120,000 to the inch have been resolved, we must have satisfactory proof that the lines of that band are ruled so close as that. Such proof can be given by photography, and when Dr. Gleason returns from Florida, where he has gone to shoot alligators, we hope he will have the band photographed and the lines counted. We shall discuss the subject of resolution more fully next month, and endeavor to indicate the value of ruled plates as tests for objectives. Just now we wish to ask some questions in regard to Mr. Fasoldt's announcement that he can rule, and has ruled, a band having 1,000,000 lines to the inch. It seems that Mr. Fasoldt sets his machine to rule lines in that proportion, and then asserts that the lines are ruled because they show the diffraction spectra. The question we wish to put to Mr. Fasoldt, and to the scientific world, is this : Are those spectra any proof of the presence of separate lines? We would like Mr. Fasoldt to inform us how fine the individual lines of his wonderful plate are ? If the plate has 1,000,000 lines to the inch, the individual lines cannot be broader than half a millionth of an inch ! Can such fine lines be ruled? Then it is a question in mechanics, whether a tool can be made so steady that it can draw a line without a tremor of half a millionth of an inch - for if not, then the lines of the plate must run together. In regard to our first question, we have already some evidence that Mr. Fasoldt's assumption is not justified. Prof. W. A. Rogers ruled a plate with his machine set for 500,000 lines to the inch, making every fifth and tenth line longer than the rest. He then measured the long lines, where they projected from the band, and found that they were so broad, that they overlapped each other, leaving no spaces between them. Evidently, therefore, the band of 500,000 lines did not consist of distinct lines. The spectra were, nevertheless, clear and bright. Hence, we are forced to conclude that the spectra do not prove that Mr. Fasoldt's plate contains 1,000,000 lines to the inch”. The Royal Microscopical Society further stated, “We have been referred to what is termed a claim of Dr. T.S. Up de Graff to have resolved lines as fine as 152,400 to the inch. Dr. De Graff's statement is, however, simply that he has resolved the last band of Fasoldt's 19-band plate, and he is careful to add “152,400 to an inch, the number of lines claimed by the maker to be ruled in this band”. While, therefore, fully accepting the observer's statement that the lines which he did resolve were true and not spurious lines, we have, of course, to wait for the demonstration that the maker's claim is correct before commencing again, with clean boards, to endeavour to establish a theory of resolution. The theoretical resolving power of the largest apertured lens yet made (Powell and Lealand's 1:47 N.A.) is about 141,500 lines to an inch”.

Up de Graff gained some notoriety among microscopists in 1883 when he testified during a murder case that a specimen of blood was human rather than dog, as had been alleged by the defense. C.H. Stowell then wrote in The Microscopist, “In a recent case on trial at Wellsboro, Pa., Dr. Thad. S. Up de Graff, of Elmira, N.Y., swore very positively on this point. The newspapers give Dr. Up de Graff the credit of convicting the prisoner. It is not the proper place here to determine whether the prisoner was guilty or not; it is in the precincts of this journal, however, to determine whether the expert testimony was according to facts. Dr. Up de Graff was given some of the stained clothing to examine, and by processes entirely unknown to the writer (according to all accounts seen), by decantations, washings, etc., some corpuscles were procured and measured. Dr. Up de Graff positively testified that this was human blood and not dog's blood. When asked if he was the only one who could tell this, he replied that “there were but four men in the world who could tell human blood from dog's blood”, and, of course, he was one of them. When asked why he could do so much better than others, the reply was, ‘On account of the superior character of his glasses, and that his microscope cost sixteen hundred dollars’. The testimony of Dr. Up de Graff makes him give a positive size to the human red blood corpuscle. What do standard writers say on this subject? Gulliver says they are the 1/3200 of an inch. Flint says they are the 1/3500 of an inch. Dalton says they are the 1/3151 to 1/3550 of an inch. Richardson says they are the 1/3376 of an inch. Woodward says they are the 1/3092 of an inch. Frey says they are the 1/3840 to 1/4830 of an inch. Welcker says they are the 1/3230 of an inch. Where is the exact size to judge by? The red corpuscles are also subject to change in size by the varying changes in the blood and by many drugs. Wagner, in his General Pathology, gives a long list of remedies that when administered change the size of this corpuscle. How delicate is it, also, to the various reagents used in microscopical work! I have seen red corpuscles as small as the 1/5000 of an inch, and as large as the 1/2500 of an inch. I have never measured red blood corpuscles in lots of fifty each and had any two exactly alike, although using a delicate cobweb eye-piece micrometer and a one-fiftieth objective. Listen to what Mr. Woodward, of Washington, says: ‘The average of all the measurements of human blood I have made is rather larger than the average of all the measurements of dog's blood. But it is also true that it is not rare to find specimens of dog's blood in which the corpuscles range so large that their average size is larger than that of many samples of human blood’. Human blood cannot be told from dog's blood, except under favorable conditions, and not invariably then. For the sake of microscopy it is a pleasure to know that only four men are ready to make such statements. There are a score of men in this country with glasses equal, at least, to Dr. Up de Graff's, who would testify directly opposite to him on this point. If Dr. Up de Graff is ready to receive a number of pieces of cloth, labeled and stained, respectively, with human and dog's blood, under favorable and unfavorable circumstances, this journal will see to it that said cloths are prepared with accuracy by competent parties. If he succeeds, he shall receive all the glory these columns can sound forth, but if he fails he will be referred gently to his Wellsboro testimony”.

Later, Up de Graff was asked directly by colleagues, “to state his position as regards the certainty of distinguishing human blood from other mammalian blood after drying in a stain or spot, by the size of the restored corpuscles. He said that he believed it possible to determine whether a given stain was human blood or not; he had made many trials, both upon stains secured by himself and upon those sent to him by others, and of the nature of which he had no previous knowledge, and that he had successfully determined which were due to human blood. He further said that he did not swear positively in a recent murder trial, as had been reported, that a stain on the garments of the accused was caused by human blood. He swore that in his opinion it was human blood”.

Blackham: “He was always willing to work hard for what he believed to be a good cause, and was careless as to who got the credit due to him. He was just, generous, affectionate and talented, and he had but one prominent fault, viz., intemperance. I do not mean that he was a drunkard, for he was nothing of the kind, but he lacked moderation. Delicate and sensitive as he was, he would sit up all night over his microscope trying to unravel some biological puzzle, and be prostrated next day with one of his terrible headaches as a consequence. In the pursuit of science, in the invention of a new surgical instrument or operation, or even in the elaboration of some whim, he never spared himself, but would go practically without food or sleep till his end was attained. In this way he accomplished much, but shortened a life that might have been prolonged for years”.

The last year or so of his life was spent in weakness and suffering; the headaches from which he had suffered from boyhood increased in severity and frequency till he was often completely prostrated by them for days at a time, and was seldom, if ever, entirely free from cephalic pain; albumen appeared in his urine, and finally at noon on the third day of August. 1885, he died calmly, peacefully, and without a struggle.

The eager, restless spirit, the keen, active intellect, the warm, impulsive, loving heart had outworn the slight, delicate body, and he died worn out ere he had reached fifty years of age. Counted by years the life was a short one; measured by deeds it was a long one. A home had been founded, a family reared, his eldest son prepared to step into his place; knowledge had been acquired, a reputation made, more than six hundred operations for cataract, twenty-two ovariotomies, the common carotid and the iliac arteries had been tied successfully, new instruments and new operations invented, and a host of the more ordinary surgical operations performed. He had won success as a physician, as a surgeon, as a microscopist, and photographer, as an author and as a public speaker; he had been up in a balloon, and down in a mine; the woods, the streams and the ocean had yielded up secret after secret to him. Honors had been thrust upon him in the various branches of the Masonic order; he had served his country on the field of battle; and, in civil life, he had been made a Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society of England, member and Vice-President of the American Society of Microscopists; had made a few enemies and hosts of friends. He was a good lover but not a good hater; he had less of bitterness in his nature than seemed possible with so decided a character. His faults were few, his virtues many. May we not hope that the restless spirit has found rest, and that in wider, fuller knowledge, with eternity before him, he learns that patience which seemed to be the only virtue he could not acquire here”.

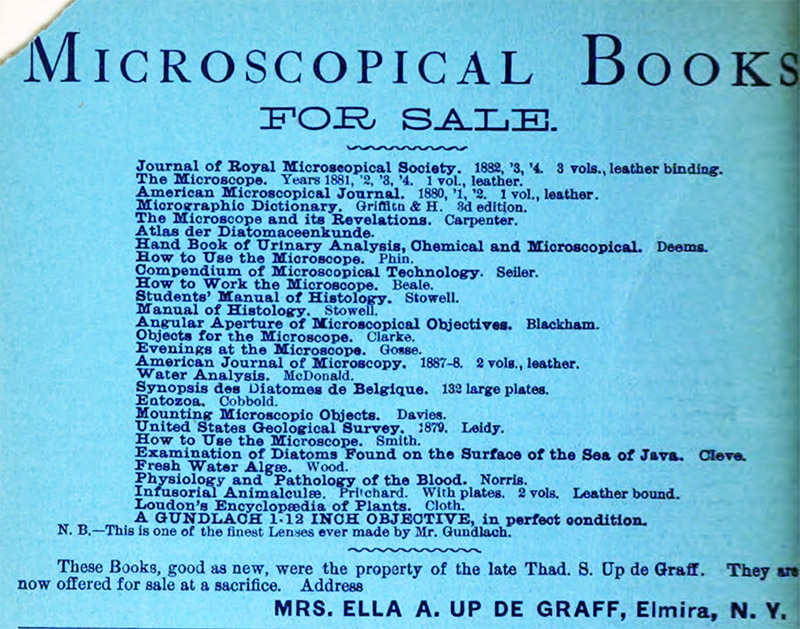

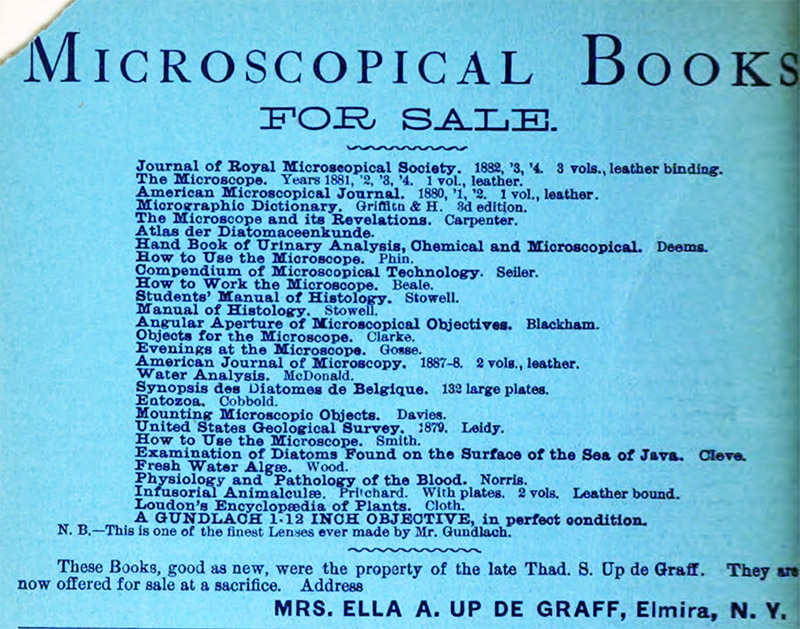

Figure 8.

An 1888 advertisement from Thaddeus Up de Graff’s widow, announcing sales of his microscope books and equipment.

Resources

American Armamentarium Chirurgicum (1889) Descriptions of surgical instruments that were designed by T.S. Up de Graff, George Tiemann & Co

The American Monthly Microscopical Journal (1882) Ruled bands, Vol. 3, pages 52-53

Blackham, George E. (1885) Memoir of Thad S. Up de Graff, M.D., F.R.M.S., Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists, Vol. 7, pages 216-222

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, page 96

The Christian Union (1878) Advertisement from T.S. Up de Graff, Vol. 17, February issue, back page

The Herald of Health (1873) Advertisement from T.S. Up de Graff, Vol. 22, page 43

Huggins, Kelly (accessed October, 2017) CSI: Elmira, http://chemungcountyhistoricalsociety.blogspot.com/2014/05/csi-elmira.html

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1882) High resolving power, page 416

Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society (1882) election of T.S. Up de Graff, page 448

Medical and Surgical Reporter (1867) Charlatanism exposed again, Vol. 17, page 213

The Microscope (1888) Advertisement for sale of T.S. Up de Graff’s books, Vol. 8, October issue, inside front cover

Miller, Barry. B. (1999) Old slides have interesting stories to tell - a case example, Micscape, http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artjul99/bmiller.html

Mott, Frank Luther (1957) “The Bistoury (1865-85) was a quarterly by T.S. Up de Graff, of Elmira, New York, ‘devoted to the exposition of charlatanism in medicine’ and to medical news”, A History of American Magazines: 1865-1885, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, page 142

Stowell, C.H. (1883) Can human blood be told from that of the Dog, Scientific American, Vol. 49, page 328

Up De Graff, Thaddeus S. (1879) Bodines: Or, Camping on the Lycoming, J.B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia

Up De Graff, Thaddeus S. (1883) Camping in the Alleghanies: Or, Bodines. A Complete, Practical Treatise and Guide to "Camping Out", J.B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia

Up De Graff, Thaddeus S. (1883) Descriptions of certain worms, Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists, Vol. 5, pages 117-119

Up De Graff, Thaddeus S. (1884) Measuring blood-corpuscles, American Monthly Microscopical Journal, Vol. 5, pages 26-27

U.S.A. official records, accessed through ancestry.com